Victims

Among the many criminals, identified and unidentified, who are household names, Jack the Ripper is in a league of his own in the popular imagination. Ever since periodicals such as "The Illustrated Police News" began to exploit his crimes for their lurid headlines in 1888, he has been conceived of as a larger-than-life stock villain in the vein of his literary contemporaries Dracula and Mr. Hyde rather than a real human being who committed awful crimes against other real human beings. As a consequence, the women he killed are frequently overlooked at best and actively insulted and exploited at worst. In remembering this case, we must take care not to mythologize and celebrate the killer; otherwise, we perpetuate the same disrespect for the victims’ humanity shown to them not only by their killer, but by the society they lived in. The Ripper case is not merely a window into the psyche of one lone depraved individual detached from historical context. It is a window into the Victorian world and the ideas about class, gender, and morality that pervaded it. To truly honor the memory of Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly, we must remember who they were in life, as well as recognize the societal forces that shaped their lives and deaths. As you peruse the records in this archive, keep their stories in mind.

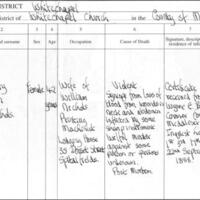

Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols (August 26, 1845 – August 31, 1888) was the daughter of a blacksmith and the wife of a printer. For a time, she, her husband, and their children lived in an apartment owned by the Peabody Trust, a philanthropic organization dedicated to providing affordable, quality housing to those members of London's working class deemed to be of good moral character. This period of relative comfort in Polly's life came to an end with her separation from her husband in 1880, likely due to infidelity on his part and/or alcoholism on hers. She would spend the next eight years in and out of the workhouse. This prison-like institution was ostensibly designed to terrorize poor people into being upstanding citizens (the idea being that poverty was a symptom of moral weakness rather than an unjust society), but in practice it merely perpetuated the very despondency that drove people to its doors in the first place (Rubenhold, 2019). Over the years Polly came to rely more heavily on alcohol. The night she died, she was turned away from a lodging-house because she couldn’t pay. Her comment that she would soon return with the necessary money gave rise to the assumption that she intended to earn it through sex. At the time, however, single impoverished women tended to be generalized as “prostitutes” (a term very freely applied), and she may just as well have intended to get the money another way (Rubenhold, 2019). When her estranged husband William came to the mortuary to identify her, he reportedly said to his dead wife, “I forgive you as you are. I forgive you on account of what you have been to me” (Rubenhold, 2019, p. 73).

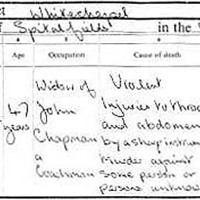

Annie Chapman (September, 1841 – September 8, 1888) did not come from a rich background, but life granted her many advantages: a good education (a perk of being the daughter of a soldier), a loving family, and a marriage to a well-paid coachman. In a letter written to a newspaper after Annie’s death, her sister explained why Annie’s life had nonetheless taken such a tragic path: at a young age, perhaps due to losing several siblings to illness and her father to suicide, she developed alcoholic tendencies—an especially difficult burden to bear in late Victorian society, in which alcoholism, like poverty, was frequently viewed as a moral failing (Rubenhold, 2019). It is likely due at least in part to her consumption of alcohol that five of her seven children died in infancy or youth; these additional tragedies, in turn, exacerbated her alcoholism. At last, her sisters convinced her to enter a sanatorium, but after a period of progress, she relapsed. At this point, her husband’s employer forced him to separate from her in order to keep his job. Annie briefly returned to her teetotaler family, but soon chose to leave them rather than give up alcohol. She relocated to Whitechapel with her common-law partner, Jack Sievy. In 1886, she was left devastated and without an income by the death of her husband, and Sievy could no longer put up with her. Even through all this, her family continued to offer their love and support, but they could never induce her to come home for long. Like Polly Nichols, the night she died, she was turned away from a lodging house. And like Polly Nichols, she was assumed (and reported by the more sensationalist periodicals such as The Star) to be a prostitute, but there is no solid basis for that assumption (Rubenhold, 2019).

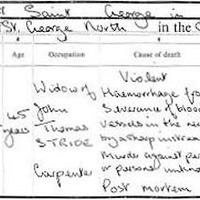

Elizabeth (or Elisabeth) Stride (November 11, 1843 – September 30, 1888) was born to a farming family in Sweden, but became estranged from them after falling pregnant as an unmarried 21-year-old. The police in the city of Gothenburg maintained a registry of women accused of sexual “immorality,” including but not limited to those who made a profession of it. Elizabeth's name was added to this list, and throughout her pregnancy the police kept a close watch over her. The cruel irony of this registry was that by ruining a woman’s name, it prevented her from redeeming herself by obtaining a respectable job, and so, after miscarrying, the only viable option left to Elizabeth was to resort to actual prostitution. Eventually she managed to make a fresh start in England, where she opened a coffeehouse with her new husband, John. The Strides enjoyed several years of success with their business, but when it failed in 1873, it took their marriage down with it. After this, Elizabeth spent some time in the workhouse, but she preferred to make money through clever scams. Most notably, from 1883 until her death, she periodically collected money from a woman named Mary Malcolm under the pretense of being her long-lost sister. In the last two years of her life, she was frequently arrested for drunk and disorderly behavior, probably due in part to the progression of syphilis. She stepped out looking nice on the evening of September 29, 1888. Perhaps she intended to solicit, or perhaps she had a date. Dozens of “witnesses” claimed to have seen her that night, but the only testimony likely to be accurate came from Israel Schwartz, who thought he had seen her fighting with a man (who he assumed was her husband) very near the spot where she was found dead shortly afterwards.

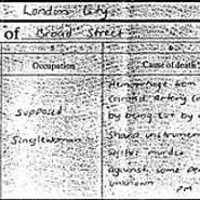

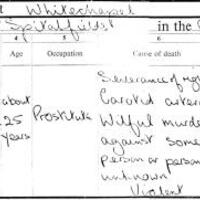

Catherine “Kate” Eddowes (April 14, 1842 – September 30, 1888), one of ten (surviving) children of a tin-worker, attended a rigorous school where she was prepared for a job in service, but such a dull, proper life did not appeal to the vivacious young woman. Instead, she took up with a traveling salesman named Thomas Conway and accompanied him on the road; the two occasionally posed as a married couple for appearances’ sake but never formally tied the knot. Eventually Kate and Thomas settled down in London, where their lives started to go downhill. Not only did they lose several of their children, but Thomas found that he was unable to earn a living in London and was forced to go further afield in search of work. It was simply not possible for a single woman to earn enough to support herself and her children, nor could an unmarried mother receive “outdoor relief,” or financial support that did not require a stay in the workhouse. (It was feared that providing outdoor relief to “immoral” women would encourage prostitution [Rubenhold, 2019]). As a result, Kate became a frequent visitor to the workhouse. To make matters worse, when Thomas was home, he was violently abusive, something his society often condoned if the wife was a heavy drinker like Kate was (Rubenhold, 2019). Ultimately, Thomas left her, taking the children with him, at which point she moved to Whitechapel and took up with another heavy drinker named John Kelly. His testimony of Kate’s last few days was muddled due to his habitual drunkenness, but at the inquest he emphatically denied that she had ever been involved in prostitution. Even though Kate’s relationship with her family had been rocky, her relatives ensured that she was not buried in a pauper’s grave, and nearly 500 people attended her funeral.

Mary Jane Kelly (c. 1863 – November 11, 1888) is a complete enigma prior to her arrival in London in 1883 or 1884. She claimed variously to be either from Wales or Ireland, but she did not speak with an identifiable Welsh or Irish accent (Rubenhold, 2019). No one has ever managed to track her family down, suggesting that “Mary Jane Kelly” was an alias. Several facts that are known about her, however, suggest that she came from a middle- or upper-class background: she was very literate, she was a skilled artist, and upon arriving in London she immediately found work in the West End in the employ of a French madam who catered to middle- and upper-class clients. While working, she met a gentleman who offered to take her to Paris; she accepted, but returned to England shortly after arriving in France. It has been speculated that this man was involved in the thriving business of trafficking women between Britain and the Continent and that Mary Jane caught on to his scheme (Rubenhold, 2019). After this incident, she moved to the seedier East End, probably to avoid enemies she had made in the West End. Mary Jane was widely known as an affable, elegant woman and generally projected a cheerful demeanor when sober, but once confided to a friend that she was “heartily sick” of the life she was leading (Rubenhold, 2019, p. 278). In 1887, she fell in love with Joseph Barnett and moved with him to a room on Miller’s Court. After Joseph lost his job, Mary Jane returned to soliciting, to Joseph’s disapproval. She further angered him by offering other prostitutes the shelter of her and Joseph's home, and he moved out on October 30, 1888. In the early morning hours on November 9, Mary Jane brought an unidentified man back to her room. Her neighbor then heard her singing “A Violet From Mother’s Grave.”