Fiction

There is hardly a scarcity of literature written about Jack the Ripper. The records in this subcategory are only a few examples of works inspired by or related to the Whitechapel murders in some capacity. All of the works included were written either shortly before or up to 20 years after the murders, which we classified as “contemporary.”

Jekyll and Hyde

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson was written three years before the Whitechapel murders and therefore could not have been inspired by the murders themselves. The connection, instead, lies with the actor, Richard Mansfield. The story had been turned into a staged production in 1888, starring Mansfield as the duplicitous main character (Flanders, 2014).

With the context of Jack the Ripper in the minds of many people in London, some theatre-goers made the connection between Mansfield’s convincing performance and the murderer at large in London. A letter was sent to Scotland Yard inquiring as to whether they would consider questioning Mansfield about the murders (Flanders, 2014). While not much came of the suspicions and there is no evidence that Scotland Yard questioned Mansfield, the rumors were enough for Mansfield himself to try to change his image. He attempted to host a “benefit performance for the Suffragan Bishop of London’s home and refuge fund” that would help employ “reformed prostitutes” ("Richard Mansfield").

The link between The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and the Whitechapel murders goes beyond Richard Mansfield. The rise in suspicion that the murders were committed by a single person who may have a medical background is used by some to exhibit the connections between public opinion on the murders and the fame of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, (Winter, 2015, p. 180-186).

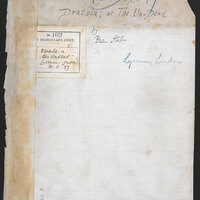

Dracula

A year after the first murder, Bram Stoker began to work on his novel, Dracula. Readers note the similarities between the story and the Whitechapel murders including the number of victims (5 women), the appearance of a "vigilance committee" similar to the Mile End Vigilance Committee, and an East End location (Flanders, 2014). It is not definitively known whether Stoker intentionally used these aspects to draw connections to Jack the Ripper, however we do know that Dracula’s depiction was based off of antisemitism at the time that similarly influenced perceptions of the Whitechapel murders.

The depiction of Dracula’s physical attributes, his status as a foreigner, his relation to the East End of London, and discussion of parasitism all map on closely to antisemitic stereotypes at the time (Halberstam, 1993). Newspapers at the time hinted at, and sometimes even outright declared that the perpetrator of the Whitechapel murders was Jewish, or, at the very least, a foreigner (Jones, 2013). An image printed in The Illustrated Police News with the label "Sketch of Supposed Murderer," for example, strongly resembles an antisemitic caricature. These fears were demonstrated even within the investigation, as released police sketches had “an undeniably exaggerated Jewish appearance” (Jones, 2013). While the link between Dracula and the Whitechapel murders may never be fully known, the antisemitism that plagues both is worth noting.

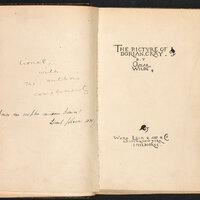

The Picture of Dorian Gray

Oscar Wilde’s novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, was published only two years after the first of the Whitechapel murders. Like The Curious Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the novel centers around a respectable man who, despite his appearances, performs horrific deeds (Flanders, 2014). Since Wilde’s death in 1900, some have put forth the idea that “Wilde may have known more than he let on about the Whitechapel murders,” (Wilson, 2013). The reasons for this suspicion seem to come from Wilde’s relationship with Frank Miles, a portrait artist put forth as a suspect in the book The Ripper Code by Thomas Toughill. This, coupled with the inclusion of a portrait artist in the novel, has led some to suspect a connection. It should be noted that there is not compelling evidence to support this claim as Miles was housed in an insane asylum 120 miles away at the time of the murders (Wilson, 2013). This lack of compelling evidence led us to exclude Miles from our suspects page.

What remains interesting in the case of The Picture of Dorian Gray, instead, is the insistence that it may be related to the murders despite evidence to the contrary. While the subject matter of the novel may have been inspired by current events in London at the time, the relationship seems to stop there. Some of this is, no doubt, due to the sensational nature of the case in popular culture but there may be more to it than that. When Oscar Wilde was “tried for homosexuality” in 1895, content from The Picture of Dorian Gray was used to question Wilde (History.com Editors). There may have been an appeal in linking a novel with a sensational story already attached to it to the murders.

In the case of The Picture of Dorian Gray and Oscar Wilde, it’s important to reiterate that there is not compelling evidence to link the book and the murders in any way other than the general theme. The reason it is included in this archive is that it is an example of the sensationalization that plagues the case and the unfortunate trend of linking the case to individuals that are considered as outsiders in some capacity.

The Lodger

The first novel written explicitly about the Whitechapel Murders was published in 1913. The Lodger by Mary Belloc Lowndes, first appearing in McClure’s Magazine in 1911, is a story about a couple running a “lodging house” who end up housing a man who turns out to be a killer, whose depiction is based on Jack the Ripper. The story comes from a friend of Lowndes who ran a lodging house and believed they may have housed Jack the Ripper (Duperray, 2012, p. 177-179). The story was a huge success and even inspired Hitchcock’s third film of the same name ("Alfred Hitchcock").

The Lodger stands apart from the other records in this section not only in the fact that it is explicitly about the murders but also in its characters. The protagonist is a woman who “is able to solve the mystery when thousands of police officers, detectives and government officials are unable to." Given the violent and sexualized nature of the crimes, Lowndes’s story can be seen as a sort of retribution against the acts themselves and the ways in which they were portrayed and handled at the time (Warkentin, 2011, p. 2).