Suspects

As the Jack the Ripper investigation gained national attention, thousands of leads and suspects came across law enforcement's desks. As so many names and stories would be too much for this archive, here are five of the most compelling cases:

Perhaps the most popular Jack the Ripper suspect among researchers, James Maybrick (October 24, 1838 - May 11, 1889) was a wealthy cotton merchant from a prominent Liverpool family. Though Liverpool is about a day's journey to London, it is important to note that all of the murders happened on the weekend, a time when someone of Maybrick's social class would not work (Background of the Maybrick Family). With a mustache and top hat, Maybrick looked like the Ripper described in eyewitnesses accounts. His death also coincided with the end of the killings, happening one year after the last murder. The piece of evidence that makes Maybrick so compelling to modern Ripperologists, though, is the discovery of a diary under the floorboards of his estate, the Battlecrease House. This diary was produced by an unemployed Liverpool scrap metal merchant, Michael Barrett, who claimed that it had been given to him by a friend, Tony Devereax, in a pub the year before he came forward with it.

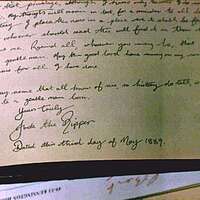

In this diary, Maybrick admits to the killings and details the murders, saying that he began terrorizing the Whitechapel district in London in a rage after seeing his wife with an unnamed lover in Liverpool's Whitechapel district. His confession ends with the quote, “I give my name that all know of me, so history do tell what love can do to a gentleman born. Yours truly, Jack the Ripper.” However, some questions have been raised about the authenticity of the diary, the most glaring ones on the subject of Michael Barrett himself. After dealing with the media circus that came with the discovery of the diary, Barrett later claimed that the diary was a hoax. A year later, however, he retracted his claim, saying the diary was real and that he did not want to deal with the press while going through a divorce. Details about how he exactly acquired the diary are vague as well (Jones, James Maybrick: The diary of Jack the Ripper).

A pocket watch found in a London pawn shop allegedly also belonged to Maybrick. It had the initials of the five canonical victims, his name, and the phrase "I am Jack" carved into the back (Jones, James Maybrick: The diary of Jack the Ripper). Although testing has determined the watch and its carvings are very old, there is no definitive evidence proving whether or not this pocket watch actually belonged to Maybrick.

The roommate of the last canonical victim, Mary Kelly, Joseph Barnett (May 25, 1858 - November 29, 1926) is the suspect considered to have had the most motive. Allegedy in love with Kelly, Barnett disapproved of her lifestyle as a sex worker, and worked hard as a fish porter in order to keep her off the streets. When he lost his job, however, she went back to prostitution to support them both (Joseph Barnett). If Barnett was the Ripper, it is believed that he started killing sex workers as a way of warning Kelly to keep off of the streets. This may have worked for a time, but with little prospects for money, Kelly went back to working as a prostitute.

On October 30th, 1888, Barnett and Kelly got into very violent fight (in which he broke a window). The fight allegedly began when Kelly brought two other prostitutes into the apartment, which Barrett deemed unacceptable. He promptly moved out, but from November 1st to November 8th, Barnett frequently visited Kelly to give her money (Joseph Barnett); this indicates that she may have had given him a key to access the apartment. Ten days later, Kelly was found murdered in her bed. After her murder, the killings promptly ended.

Barnett, having previously lived in at least ten different locations in Whitechapel, would have had no problem navigating back roads to evade the police. He also fit contemporary witness descriptions and the FBI's 1988 psychological profile of the Ripper (Douglas, 1988). It is alleged that his friends called him "Jack", too.

It is also worth mentioning that the famous "Dear Boss" letter signed by Jack the Ripper mentioned ginger beer bottles, of which Barnett had thirteen when police searched his home (Joseph Barnett). The FBI postulated the Ripper stopped killing either because he was arrested for a different crime, or because he grew afraid that he was close to being caught (Douglas, 1988). Barnett was arrested and questioned before being let go. It is theorized that with the motive behind his murders gone and police close to catching him, Barnett may have ceased all illegal activity and tried to throw suspicion off of himself.

An impressionist from Germany, Walter Sickert (May 31, 1860 - January 22, 1942) had a keen interest in the crimes of Jack the Ripper, making them the subject of at least two of his paintings (Hoffler). He was also known to dress like witnesses' accounts described Jack the Ripper's clothing. Sickert, nonetheless, was not considered a suspect until the 1970s, when various researchers maintained that he was either the killer or an accomplace (Hoffler). The most prominent of these theorists is Patricia Cornwell, an American crime writer who has spent years researching the Jack the Ripper case.

There are two key pieces of evidence that support Cornwell's belief that Sickert is the Ripper. The first is a discovery from Cornwell and her team, who believe they have found Sickert's DNA on Jack the Ripper's letters (Hoffler). Sickert's DNA, however, no longer exists as a complete sequence, as his body was cremated after his death; the best DNA forensics experts could attain come from his descendants, which makes these results inconclusive at best (Hoffler). The second piece of evidence is that specific watermarks on his paper were matched to the letters sent to police. Nevertheless, most of the letters sent to the police during this time -including the letters the tearm used as evidence- are considered hoaxes (Nini, 2018, p. 623). Bizarrely, though this does cast doubt that Sickert committed the crimes, it also implies that Sickert did have a hand in sending the hoax letters taunting the police.

Aaron Kosminski (September 11, 1865 - March 24, 1919) was a Polish-Jewish barber who had immigrated to London between 1871-1873. Little is known about his life in London, except that at some point he became a successful tailor and had a known hatred of women and prostitutes. Sir Melville Macnaghten, Assistant Chief Constable of the London Metropolitan Police, and two other top dectectives on the Jack the Ripper case strongly suspected Kosminski, especially after an eyewitness allegedly came forward indentifying Kosminski as the Ripper (Jones, Aaron Kosminski; House, 2005). However, Kosminski was never arrested due to the witness' hesitance to testify, saying that they did not want to sell out "a fellow Jew", a testament of London's rampant antisemitism at the time (Aaron Kosminski; Flanders, 2014).

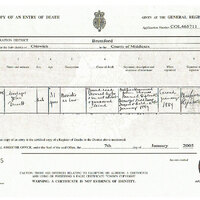

By mid-1890, Kosminski was displaying signs of severe mental illness, being admitted to an asylum for three days in July of that year. He was admitted to another asylum, Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum, in Febuary of 1891. The supposed cause of his insanity was "unknown", but "self-abuse" was later listed in institutional records. Significantly, this same admissions book noted that Kosminski was not a danger to others, yet describes how he previously threatened his sister with a knife (Jones, Aaron Kosminski). In April of 1894, he was transferred to Leavesden Asylum, where he spent the remaining twenty-five years of his life (House, 2005). A DNA test, recently conducted on a shawl that allegedly belonged to one of the victims (Catherine Eddowes), supposedly proved Kosminski's guilt, however a major testing error throws the validity of those results into question (Adam, 2019).

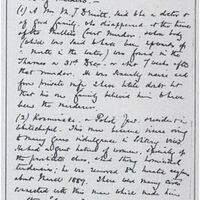

Montague John Druitt (August 15, 1857 - December 31, 1888) was the favoured suspect of Assistant Chief Constable Macnaghten. In his Memorandum, Macnaghten lists three suspects whom, he claims, were likely to have been Jack the Ripper. One of them is Aaron Kosminski, while another is "a Mr. M. J. Druitt" who Macnaghten describes as having been

“...a doctor of about 41 years of age and of fairly good family, who disappeared at the time of the Miller's Court murder... From private information I have little doubt but that his own family suspected this man of being the Whitechapel murderer, it was alleged that he was sexually insane" (Montague John Druitt; Jones, Montague John Druitt).Druitt worked as a barrister and added to that income by working as an assistant schoolmaster at a boarding school in Blackheath, Southeast London. At the end of November 1888, for reasons still unkown, Druitt was suddenly dismissed from the school (Montague John Druitt; Jones, Montague John Druitt). A month later, on December 31st 1888, his body was found floating in the Thames, where it had been for some time. The timing of his suicide would explain why the murders ceased after Mary Kelly was found dead in Miller's Court. Druitt's involvement in the murders became far more likely after news spread that his family believed he was the Ripper (Jones, Montague John Druitt). For many years, many historians were convinced of his guilt and Druitt was the suspect of choice to many Ripperologists.

Yet under scrutiny, Macnaghten's theory falls apart due to several critical errors. The first is that Druitt was ten years younger than the Constable claimed, being 31 instead of 41 when he died (Jones, Montague John Druitt). Also, though many in Druitt's family were doctors, he wasn't himself. Macnaghten claims that Druitt's mind was unstable and cracked after Mary Kelly's murder. However, Druitt seemed to be mentally stable in the following weeks, as he continued working as a barrister after the last murder and continued to work as a teacher at Valentines School until his dismissal at the end of November, three weeks after Kelly's death. In addition, another prominent detective on the case, Chief Inspector Fredrick Abberline, did not see Druitt as a viable suspect (Jones, Montague John Druitt). Nothing known about Druitt implies that he visited Whitechapel during his lifetime or had any special knowledge of the area- a key flaw in Druitt's characterization as a guilty Ripper suspect.