Correspondence

Letters, postcards, and other mailed notes have played a key role in early investigation of the Whitechapel murders and the news spread about it.

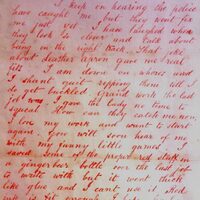

On September 25, 1888, a letter addressed “Dear Boss” and written in red ink was received by mail at the Central News Agency in London. In it, the author takes responsibility for the murder of Annie Chapman on September 8 and taunts investigators, commenting that an ear would be cut off of the next victim and mailed to London Metropolitan Police (Scotland Yard). The fact that the ear of following Ripper victim Catherine Eddowes was found to be missing after her murder on September 30, when that information had not yet been released to the public, indicated to police that the “Dear Boss” letter was a genuine communication from the murderer. Though researchers and forensic analysts have largely concluded that the note was a hoax and did not come from the perpetrator of the crimes, the letter’s salutation, “Jack the Ripper”, has provided the pseudonym used by the press for the killer (Nini, 2018; Morrison, 2019).

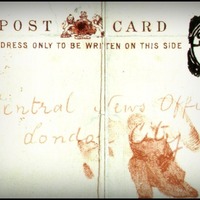

A few days later, on October 1, 1888, the Central News Agency received a second communication from Jack the Ripper, this time a stained postcard now known as the “Saucy Jacky” card. The author, “Jack”, apologizes for not sending an ear and claims responsibility for two Whitechapel murders that occured the night before, those of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes. Investigators at the time believed again that this note could have come from the actual murderer, considering the coincidental timing between the September 30 killings and the arrival of the card, and released copies of both the “Dear Boss” and “Saucy Jacky” notes from October 3-4 on posters and in newspapers (Nini, 2018). Scotland Yard received hundreds of letters over several years following the publication of this correspondence, many of which came to be viewed as hoaxes. Today, there is limited evidence outside of some handwriting analysis to prove either any connection between the “Dear Boss” letter and the “Saucy Jacky” postcard, or that their author(s) could have killed Chapman, Stride, and Eddowes.

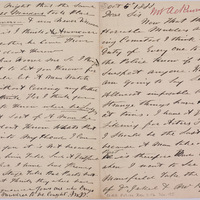

Some of those later letters went so far as to accuse famous Englishmen of being Jack the Ripper. An anonymous letter sent to the City of London police on October 5, 1888 argues that celebrated actor Richard Mansfield could be the killer (Letter to City of London Police about Jack the Ripper). Mansfield was well-known during the era for the portrayal of the alter-ego main characters in a London play adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Hyde is just one example of the literary monsters that fascinated British society in the late nineteenth century and stimulated ideas about Jack the Ripper in the public imagination.

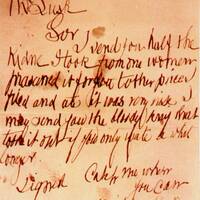

Hoax mail signed “Jack the Ripper” was also sent to investigators outside of the media and police forces. George Lusk, the head of the Mile End Vigilance Committee (a local Whitechapel militia group), received the “From Hell” letter on October 16, 1888, accompanied by half of a kidney. While Catherine Eddowes had indeed been missing a kidney when found two weeks earlier, there was no proof that the contents of Lusk’s package belonged to her (Treasures: Jack the Ripper). Authorities ruled the letter and package a hoax, but the “From Hell” letter and its earlier counterparts remain central pieces of potential evidence compiled in the search for Jack the Ripper’s identity.