Newspapers, Political Cartoons, and Other Periodicals

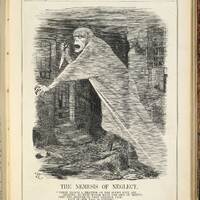

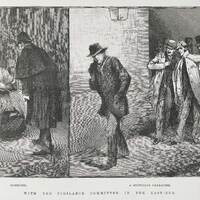

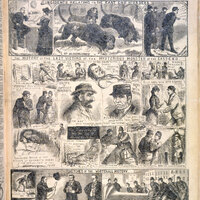

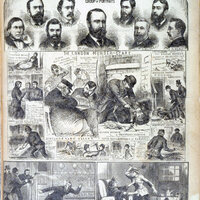

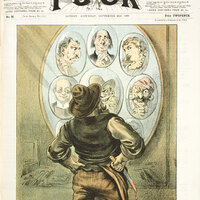

Journalism about Jack the Ripper and his crimes both informed the public about investigations into the 1888 Whitechapel murders and sensationalized public perceptions of the police and the killer. Following the discovery of the “Dear Boss” letter and its publication in the press, newspapers, political cartoons, magazines, and other periodicals were the first to refer to the Whitechapel murderer as Jack the Ripper, and the name caught on. They also played into public worries and stereotypes about immigration, poverty, and poor morals being the root of the killer’s crimes (Morrison, 2019, p. 52-55). As historian Drew Grey attests, “it was the addition of an intense media interest in the case, and the juxtaposition of this with contemporary debates and fears, that catapulted this murder series into a global phenomenon” (2018, p. 3). Without much direct evidence available to help catch the Ripper, public imagination and media exaggerations alike made it difficult to determine which information about the case was fact, and which was fiction.

Journalists for periodicals across the political spectrum began to connect the various killings as the work of one perpetrator, sharing evidence about ongoing investigations and spreading rumors about the case and the suspect’s appearance as newsworthy facts. Conservative, Tory newspapers like The (London) Times and The Essex County Standard frequently focused on details of the crime scenes, the dangerous nature of the Whitechapel district, and the lack of progress by the police in tracking down the killer. Periodicals and satirical cartoons on the liberal to radical end of the political spectrum, such as The Observer and The Illustrated Police News, emphasized new developments in the case and characterized Scotland Yard as incompetent, biased, and clueless. While well-established weekly newspapers tended to share more factual narratives than daily papers or tabloids, media of all types brought attention to “misleading information” (Morrison, 2019, p. 46; Johnson). Such portrayals of the crimes, their locations, and the work of authorities to solve the murders kept the public interested in the case and helped news of the killings to grow to a sensational level.