Arthur Rackham in Historical Context

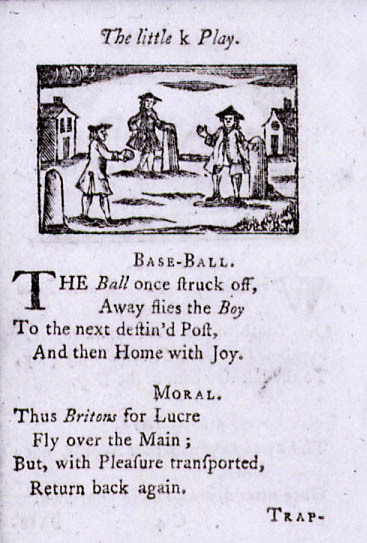

The history of children’s literature in Europe and the United States is inexorably tied to the history of childhood as a concept. While adults had been sharing stories with children for a long time, children’s literature (the genre of books published for the entertainment of children) did not emerge as a popular literary genre until around the eighteenth century. Before such a genre could emerge, Western society had to develop a new understanding of children as worthy of such attention. During the religious movements of the Early Modern period, religious groups like the Puritans regarded children as inherently tainted by original sin and in need of strong corrective action rather than frivolous entertainment (Sommerville, 1990, p. 120). It took secular thinkers to devise a concept of childhood which regarded children as innocent and free of sin. As this intellectual trend began to appear among groups like the Cambridge Platonists, growing as the Enlightenment took hold across Europe, printed books became widespread as literacy grew and the printing press proliferated across Europe. Many historians regard Enlightenment-era thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s 1762 novel, Emile as a turning point. This widely read novel portrays a creative young boy and his tutor. Taking cues from this novel, many in the West then argued that children possessed a natural goodness and that authority figures ought to cultivate their creativity rather than crush it with harsh discipline as in previous eras (Sommerville, 1990, p. 128). At the same time, cheaply printed popular literature, called “chapbooks,” arose. Some of these chapbooks contained literary retellings of popular fairy tales (Heywood, 2001, p. 167). While these tales were considered to be good entertainment for all ages, they would provide the framework for later authors to create children’s literature as a genre. Knitting together all of these currents, John Newberry published what is widely considered to be the first children’s book: A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, intended for the Amusement of Little Master Tommy and Pretty Miss Polly with Two Letters from Jack the Giant Killer (1744). While this book contained educational elements, Newberry made it clear that, with this book and with later works like Mother Goose Tales and Robinson Crusoe, he intended to both instruct and entertain the children readers (Heywood, 2001, p. 166). As the genre grew and the century progressed, figures like Hans Christian Anderson began to write down medieval fairy stories in forms that we would recognize today. Finally, as the 19th Century developed and as the children’s book genre grew into an even more massively lucrative business, the teaching function of children;s literature began to fall by the wayside. Children’s books became pure entertainment, forging the era which many call the ‘Golden Age’ of children’s literature (Heywood, 2001, p. 168).

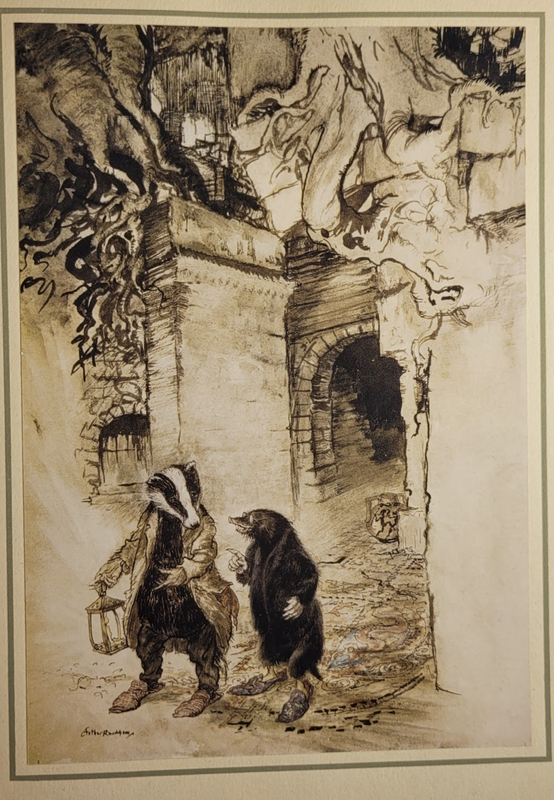

Arthur Rackham became one of the most influential artists of late Victorian-era Britain—the height of the ‘Golden Age’ of Children's Literature. At this time, the concept of childhood was rapidly changing. Child-like attributes such as innocence and curiosity were being seen as serious inspirations for education and creativity (Artful Dodgers 151, 152). Rackham's illustrations exist in the worlds of Kenneth Grahame's Winds in the Willows, or Lewis Carol's Alice in Wonderland and many others, extolling the perspective of adventurous children and plucky heroes that teach and entertain. By his death in 1939, Rackham had illustrated many of Britain's most beloved children's books, which would not only help spark the imaginations of millions of children, but would help popularize the modern notion of childhood. Rackham is regarded as the greatest illustrator of children's stories at this time. He and other artists' popularity was helped by the advent of a new technique of illustration printing called the three-color process (Ray 203). This technique simplified the process needed to accurately print color illustrations, allowing artists to create more vividly colorful illustrations than ever, and for Rackham to develop his famous watercolor style. Although Rackham was a latecomer to the golden age of children's literature, he was its most famous artist, and his work illustrated a remarkable new "insight into the minds and feelings of children", an ability which has influenced children's literature and illustration ever since (Ray 204).