The Renaissance through the 17th Century

The Renaissance saw a resurgence of the Classical arts and the birth of humanism (Smalls 2008). The humanists were interested in reconnecting the Classical stories they were familiar with their pederastic origins, as well as with the conservative Christian and Catholic themes that had prevailed in art and society for the past millennium. In Italy, one of the hearts of the Renaissance, humanism led to the increasing toleration of hedonism and bisexuality as Classical values. Classical myths dignified homosexual intercourse, and artists were both privately and publically homosexual.

As the prevalence of public homosexuality increased, so did the repression of homosexuality. In Venice, the Signori di Notti and then the Council of Ten prosecuted cases of sodomy and sentenced those found guilty to corporal punishment and execution (Ruggiero 1985). Religious fundamentalists increased with the Protestant Reformation, during which time both the Protestant and Catholic churches became increasingly strict in their moralizing.

Many of the great Renaissance artists engaged in homosexual intercourse throughout their career– at least three out of the four Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (famously named after Renaissance artists) are named after artists who were attracted to men (Smalls 2008). Some artists explicitly embraced their homosexuality– Giovanni Bazzi was referred to (and referred to himself) as "Il Sodoma"– "The Sodomite".

In general, female homosexuality in art was relegated to bathhouse scenes (Smalls, 2008). This is a continuity of the lack of women and queer women in art.

Return to Classical Narrative

The art of the Renaissance returned to Classical Narrative along with philosophy and literature. The queer stories that were told in the Ancient world were retold by queer artists– the relative recency of the stories allows us to know the biographies of the artist and understand the work through that lens.

Alexander the Great, Roxana, and Hephaestion

Alexander the Great's relationship with his companion, Hephaestion, frequently serves as a queer narrative. While it can be heterosexualized with Alexander's marriage to the princess Roxana, artistic tools were used by queer artists to show the queer narrative within the straight one. For example, in a fresco for Agostino Chigi's mistress's bedroom, Il Sodoma portrays the marriage of Roxana and Alexander – a heterosexual marriage. However, the artist (who described himself by the nickname Il Sodoma at the time – publicly announcing his sexual proclivities) told a bisexual narrative as well (Saslow 192). Hephaestion stands with the god of marriage, Hymen. Both Alexander and Hephaestion are based on the Apollo Belvedere, a statue of the "most vigorously bisexual of the gods" (Saslow, 192). Along with the rest of the cycle of frescoes and Bazzi's reputation, we can view the creation of this work as a queer artist being commissioned to create a queer work of art.

The Queerification of Christian Narratives

In the Middle Ages, we can see some homosexual narratives in art when looking back at them through a modern lens. In the Renaissance, where we know of homosexual artists, we are able to more explicitly read homosexual desires and themes in their art. Through their artistic choices, artists transformed Christian narratives into homosexual ones.

David and Goliath

In the story of David and Goliath, the young future king kills the giant Goliath. In the Renaissance, queer artists like Donatello remade the narrative into a pederastic one – James Saslow writes about how Goliath "lost his head" over the young David, and the figure is reminiscent of Ganymede standing above a feathered Jupiter (Smalls, 59).

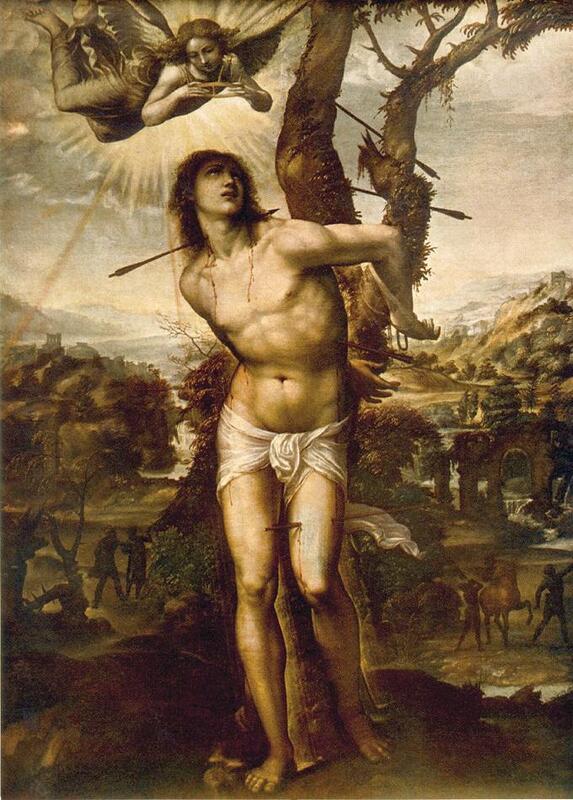

Saint Sebastian

Saint Sebastian was a martyr who was targeted for his devotion to Christ. He became a popular icon in Christian art, particularly of the attempted execution. In this narrative, he is tied to a post and shot with arrows for his religious beliefs. Following his recovery, Sebastian approached Diocletian (his beloved according to some accounts) and was executed for his impudence (Saslow 2013 139; Doble 2020).

In the Renaissance, artists shifted from portraying Saint Sebastian as a more masculine and mature figure to a younger, handsome one (Doble 2020). Art historian James Saslow describes Saint Sebastian's passionate "all-consuming, spiritual-erotic love of Christ" (1977) that became a homoerotic trope. In Il Sodoma's portrayal, Saslow says, an androgynous, Apollo-like Saint Sebastian is in an ecstacy-agony as he is pierced by phallic arrows, gazing at his beloved male God. The LGBT+ claiming of Saint Sebastian has persisted to today, where his persecution can be seen as a coming out narrative– the androgynous man persecuted for his love of another (Doble 2020).

Homosexuality in Chinese Literature

Emperor Ai and Dong Xian

In a different part of the world, during this same timeframe but separate from the Western conception of the Renaissance - China was in the midst of a transition between the Ming Dynatasy (1264 - 1644 CE) to the Qing dynasty (1644 - 1912). During the Ming dynasty open sexual expression flourished (Hinsch, 1990, p. 139), and there was an awareness of the long tradition of male homosexuality in particular (p. 119). Male homosexuality was present for thousands of years in Chinese history (Rahman 2019), which Westerners had long noted as being commonplace and used to stroke homophobic distrust of the country (Hinsch, 1990, p. 1-2). While female queer relationships were largely ignored in traditional sources (p. 174), even the shift to the more conservative and sexually restrictive Qing dynasty did not erase the long standing tradition of male love in popular literature (p. 147).

It was in the context of this societal movement that Chen Hong Shou in the year 1651 CE painted the famous story of the passion of the cut sleeve (Rahman 2019). The Chinese Emperor Ai of the Han dynasty, historian Ban Gu said, "by nature ... did not care for women" (Hinsch, 1990, p. 53), and became famous for his love affair with his favorite Dong Xian. According to one account:

[Xian] used to sleep with the emperor. Once, he was taking a nap and was lying on a sleeve of the sovereign's robe. The sovereign wanted to get up, but Xian was not

yet awake. Thus, not wanting to shake him, the emperor cut off his own sleeve, and then got up: so great was his love! (Vitiello, 1992, p. 343-344)

This imagery was striking, and for ages to come "cut sleeve" would be way for Chinese people to describe male homosexuality (Hinsch, 1990, p. 52). This painting depicts the tender moment between the two.