The Ancient and Medieval Worlds

Homosexuality and homosociality, and stories about homosexuality/homosociality, have existed for millennia. Diversity in sexual orientation can be seen back to the ancient world, although prejudices against homosexual relationships can also be seen.

Ancient Egypt

Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep

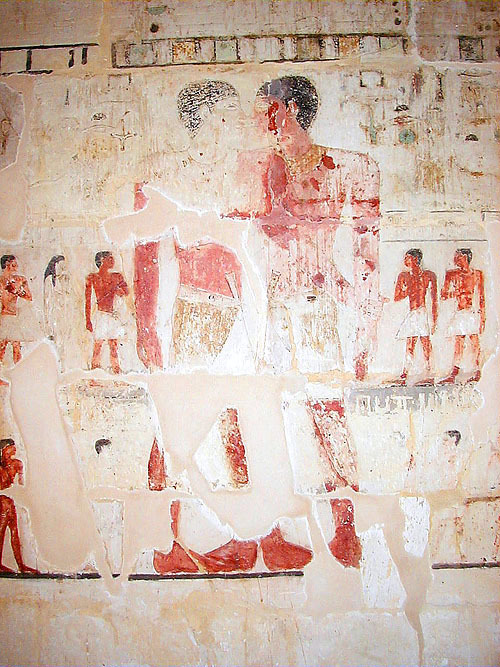

Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep “are believed by some to be the first recorded same-sex couple in history” (Ochella et al., 2012, p. 21). The two lived under the Fifth Dynasty of Old Kingdom Egypt (Reeder, 2000, p. 163), which is circa the 24th century BCE. They were royal servants who shared the title of “Overseer of the Manicurists in the Palace of King Niuserre” (Ochella et al., 2012, p. 21).

Their joint tomb was discovered in 1964 and immediately captured attention because of how the carvings on the walls depicted the two men in a close embrace. “Initial archaeologies suggested the two men were close friends, but soon the idea of them as twins was being advocated to explain their 'exaggerated affection’” - a view that still persists with some scholars, though there is nothing in the tomb describing a biological relationship. However, other archeologists have noted the intimate poses usually found in iconography of husband and wife (Reeder, 2000, p. 195).

References to homosexuality in Ancient Egypt are sparse; there was a strong emphasis on the ideal Egyptian family of a mother, father, and children (Reeder, 2000, p. 205). While both men did have wives, their presence is minimal, with Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep depicted together in places where it would be traditional to see a married couple (Ochella et al., 2012, p. 21). The most famous image of the two men depicts them in an embrace with their noses touching, with their lower torsos so close together that the knots on their belts are touching. This purposeful eschewing of the relationship between husband and wife in favor of the relationship between Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep is striking given the religious belief that their tomb would be their eternal resting place and shows a desire for them to be forever linked (Reeder, 2000, p. 205).

Ancient Mesopotamia

Gilgamesh and Enkidu

The Epic of Gilgamesh (13th-11th centuries BCE), is a poem about the journeys of the king of Uruk, Gilgamesh (Parkinson, Smith, & Carocci, 2013). To prevent Gilgamesh from oppressing his people, (Spar, n.d.) the gods create Enkidu to be his companion. Gilgamesh is told:

A strong partner will come to you,

One who can save the life of a friend...

You will love him as a wife, you will dote on him.

(Parkinson, Smith, & Carocci, 2013)

Gilgamesh and Enkidu, who is described as looking almost identical to Gilgamesh, travel to fight the giant Humbaba, who protects the sacred trees of the Cedar Forest. (Spar) Following Gilgamesh and Enkidu's triumphant return to Uruk, the goddess Inanna (also referred to as Ishtar by other civilizations) propositions Gilgamesh, who refuses her advances. In response, Inanna sends a Bull of Heaven to destroy Uruk and punish Gilgamesh. After Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the bull, the gods make Enkidu fall ill and die. This leads Gilgamesh to go on a journey to become immortal.

It can be difficult to identify Gilgamesh in some stories, as the way he is depicted can be similar to the god Lahmu.

Ancient Greece

Content warning: pedophilia

Pederasty was the homosexual and homosocial relationship between an erastes and eromenos– an older man and adolescent boy, respectively – common in the gymnasia and battlefields of ancient Greece (Smalls, 2008). The erastes would teach the eromonos manhood and citizenship. This relationship was an exception to the usual scorn that was frequent in examining homosexual relationships, as the pre-existing power dynamic removed the scorn that would otherwise be assigned to the eromenos. Pederastic relationships are present throughout Greek mythology, and the artwork based on it. A lot of the artwork on pederastic relationships is vases, as it was common for the erastes to commission a vase for the eromenos as a part of the courtship process.

Achilles and Patroclus

In the Illiad, Homer tells of the pederastic relationship between Achilles and Patroklus. Achilles, the most handsome and noble of the ancient Greek warriors, is distraught at Hector's killing Patroklus, so he avenges his death, killing Hector and dragging his body behind his carriage (Kesteren, 2019). While this is described as a friendship more than a romantic or sexual relationship, readers throughout history view the relationship as a pederastic one (Smalls, 2008).

Achilles and Petraklus first appear in artwork in the late 6th century in black-figure and red-figure vases.

Women

Sappho, from whom the words sapphic and lesbian both come (she was from Lesbos), was a poet and teacher at a thiasos (Smalls, 2008). Ancient writings generally do not mention that she was a lesbian, and Hellenistic and Roman works refer to her as bisexual or even heterosexual. Sappho can be seen in art starting 100 years after death. While some art, like busts, is not narrative, other art, like a vase showing her teaching, references her biographical narrative and, perhaps, the narratives told in her poetry (Yatromanolakis 2001).

The Amazons, the female warrior women from the East in ancient Greek mythology, are featured on several vases. However, though the Amazons can be seen as homosocial in their matriarchal and "man-killing" society, the mythology surrounding them is not explicitly homosexual (Mayor, 2014). In fact, historian Adrienne Mayor claims that one of the few seemingly lesbian vases depicting Amazons is actually indicative of male homosexual seduction (135-137).

Ancient Rome

In ancient Rome, the taboo against anal sex was so strong that pederastic relationships were forbidden, and are not seen in art (Smalls, 2008). However, by the 1st century CE, the taboo lessened, and we know that many emperors partook in pederastic and other homosexual activities. The story of Zeus and Ganymede was adapted into the story of Jupiter and Ganymede, or Catamitus, and was appreciated by the Romans.

Hadrian

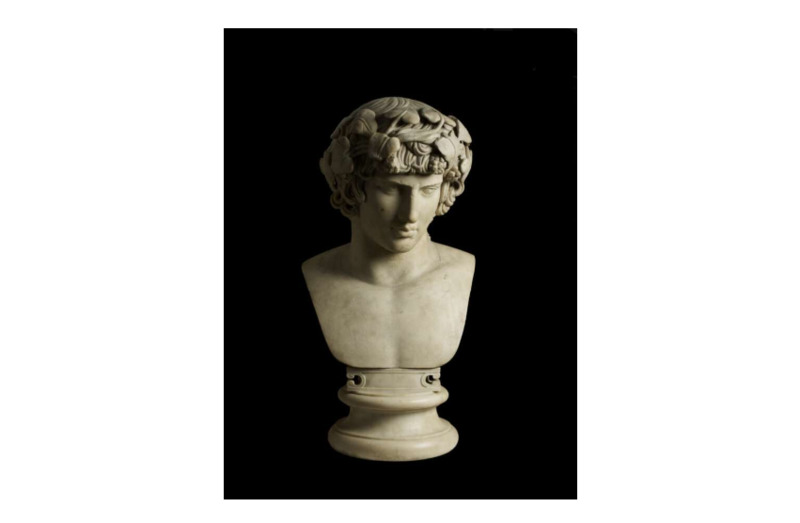

The Roman Emperor Hadrian fell in love with Antinous, a handsome Bithynian young man. Hadrian was bereft after watching Antinous mysteriously drown in 130 CE. Hadrian deified him following his death and memorialized him through naming a city after him and commissioning statues, coins and medals throughout the empire.

Statues of Antinous from Hadrian's life show him as a young man, which, in context of his relationship with the bearded Hadrian, labels him as an eromenos (Smalls, 2008).

The Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, both male and female homosexuality became punishable by the death penalty in the Christian West (Smalls, 2008). Capital punishment for homosexuality remained in most Western European countries until the late eighteenth century. Sexual lust and relations for purposes besides procreation were both condemned by the Church, so homosexuality was doubly attacked.

Most art was religious, and art depicting any sexual acts, especially homosexual acts, were heavily discouraged or even attacked by the church. Early Christian art depicted homosexuality as amicitia or sodomia. (Smalls, 2008) Amicitia was a chaste and close relationship, perhaps closer to homosociality, while sodomia is a term that censured homosexuality and other sexual themes. While the Church was never tolerant of homoexuality during this time period, there were times when it was ignored, as well as times when it was more vigorously attacked.

Sodom and Gemorah

Content Warning: homophobia

In the Biblical story of Sodom and Gemorrah, God punishes two cities for being wicked (Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures, 1985, Genesis 13:13). In the medieval era, the wickedness of Sodom was believed to be homosexuality, leading to "sodomy" being used as a euphemism for gay intercourse (Smalls, 2008). While there are a few examples of Sodom and Gemorrah being portrayed in visual art, in general, homosexuality was so unimaginable that it was not portrayed in art at all.

Medieval Homosocialities

While positive homosexual narratives are missing from the medieval canon, various homosocial stories were highlighted as model relationships (frequently in a higher standing than sexual relationships, which were base and earthly). Although these stories may, have been reclaimed by the LGBTQ+ community today, when read in the medieval context,they are stories of ideal friendships, rather than romances or sexual relationships.

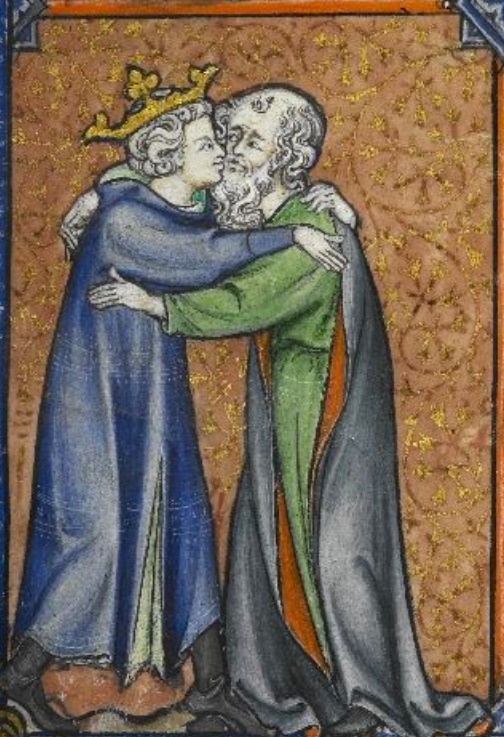

David and Jonathan

In the Bible, David meets Jonathan, the son of King Saul, after defeating Goliath. Samuel I says that "Jonathan’s soul became bound up with the soul of David; Jonathan loved David as himself... Jonathan and David made a pact, because [Jonathan] loved him as himself." (Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures, 1985, I Samuel 18:1). As King Saul becomes jealous of David and schemes against him, Jonathan protects David, their love for each other also continues, and the importance of their bond is repeated.

When Jonathan is killed in battle, David cries

I grieve for you,

My brother Jonathan,

You were most dear to me.

Your love was wonderful to me

More than the love of women.

(II Samuel, 1:26)

We do not see queer readings of David and Jonathan's relationship until later centuries, but their relationship was seen as a model for homosocial friendship throughout the medieval period. They were popular icons in the thirteenth and fourteenth century illuminated manuscripts.

Jesus and Saint John the Beloved

Jesus and Saint John the Beloved (Saint John the Evangelist) are frequently depicted in a physically intimate homosocial scene, with John's head on Jesus's chest. They are in this embrace in reference to the Last Supper, during which Saint John, "who Jesus loved," leaned on Jesus's chest. (Cleveland Art Museum) They were seen in twelfth to thirteenth century manuscripts, and were popular in 1300-onward German sculpture (Smalls, 2008). There are many modern queer interpretations of Jesus and Saint John the Beloved.

Mary and Elizabeth

Women's marginalization during the Middle Ages has led to them being underrepresented in historical documentation and art (Smalls, 2008). We know from legal codes that female homosexuality was forbidden, but there is less documentation surrounding it. Like with men, though, we know that homosociality was encouraged, both through a letter from Saint Augustine to a community of nuns distinguishing between the forbidden homosexuality and acceptable spiritual relationships.

Just as the story of David and Jonathan was used as a model for male homosociality, Mary and Elizabeth, through the story of the Visitation, were a model for female homosociality. This story is told in Luke I, in which Mary visits her cousin Elizabeth, both of whom have been told by the angel Gabriel that they will have a son (Jesus and Saint John the Baptist, respectively. As Mary is a virgin and Elizabeth is barren, both births are results of divine interference. From the ninth century onwards, depictions of the visitation have shown Mary and Elizabeth embracing each other (Smalls, 2008).

Becoming Christ as a Genderqueer Narrative

In the Middle Ages, Christians would attempt to be Christ-like. For women, being like Christ sometimes went a step further, as they saw themselves becoming Christ on the cross (Friesen 2001, 26). At times, they were described as a "woman Christ," but there are also stories of Catherine of Siena being seen in a vision by a male contemporary as "bearded and Christ-like; she herself, in turn, envisioned that she was being nursed at Christ's breast" (Friesen). In these narratives, we both see female saints becoming more masculine as they become Christlike, and Christ becoming more feminine through maternal metaphor. Why this happened is not completely known – it could have been referencing more feminine pre-Christian depictions of ancient gods with feminine characteristics, or been encouraged by women, who identified with Christ. Ilse Friesen suggests that more feminine Romanesque depictions of Christ with slight breasts (which may have looked like the Volto Santo de Lucca below) , were later "recarved, renamed and clothed in fashionable female costumes," erasing the previous femininities (29).

Wilgefortis

The feminization of these Christ figures led to new legends being created, like that of Saint Wilgefortis.

In the late Middle Ages, the saint Wilgefortis was created, possibly in reaction to cross-dressed, standing depictions of Christ, like the Volto Santo (2013, Wallace 2014). In the legend (Wilgefortis is generally presumed to be a fictional creation), Wilgefortis was the daughter of the pagan king of Portugal. Wilgefortis and her siblings converted to Christianity, and Wilgefortis took a vow of virginity. (Farmer 2011) When her father demanded she marry the king of Sicily, she prayed to become unattractive to avoid the marriage, and grew a mustache and beard. When the king withdrew his offer of marriage, her father had her crucified.