Allied Intervention in The Russian Civil War

The Polar Bear Expedition

As World War I—the largest, deadliest conflict to date—was reaching its coda, internal strife within the nation of Russia was at a boiling point. Brought on by food shortages and a depleted national morale from the immense casualties suffered during the still-ongoing war, massive protests materialized in the streets of Russia’s Petrograd (now St. Petersburg), resulting in the abdication of the current monarchy and months of political turmoil. The friction culminated in the Soviet Communist Party taking power, sparking the Russian Civil War in November of 1917.

Ultimately marking the beginning of over 70 years of Soviet rule, the Russian Civil War was undoubtedly a prominent moment, yet somewhat obscured by the significance of the still ongoing WWI. Truly obscured is the Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War, which saw Allied forces contending with the communist Bolshevik party. Initially an effort to prevent weapons and supplies from falling into German hands, the Allied Intervention soon turned into an anti-communist effort after the Bolshevik Party signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Germans, signifying their exit from WWI—a betrayal to Allied Forces, sparking tensions between the U.S. and soon-to-be Soviet Union that would eventually lead to the Cold War.

American participation in the Allied Intervention, which came to be known as the Polar Bear Expedition, began in September of 1918 at the request of the British and French. The troops destined for Russia docked in Achangel, fresh from training. These soldiers, known as the 85th Infantry Division, mostly originated from Michigan, braving the infamous Russian terrain for a year. Soldiers questioned their objectives after fighting with the Red Army against the Central Powers, contributing to a growing sense of disillusionment felt by many in the wake of a war that broke international treaties and saw 40 million casualties, of which up to 13 million were civilians.

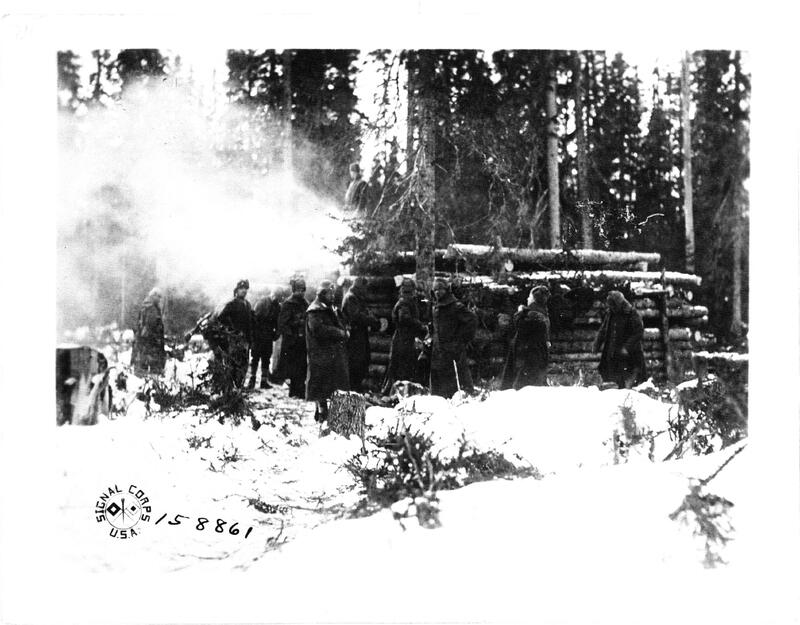

For the soldiers of the Polar Bear Expedition, the cold was as lethal as a bullet. Temperatures regularly plummeted below -40°F, freezing exposed skin in seconds and turning breath into ice. Snowfall blanketed the dense forests and open fields constantly, making movement slow and exhausting. Frostbite was a constant worry, with the threat of losing a finger or toe—or worse—always looming. Even routine tasks like loading weapons or preparing rations became grueling battles against the cold. Their uniforms, designed for Europe’s climate, offered little protection against Russia’s arctic onslaught. Men wrapped themselves in scavenged furs or tattered blankets, but there was no true defense against the relentless freeze. It permeated their bones, sapping both strength and morale. The cold was not a backdrop to their fight, but rather one of the worst enemies.

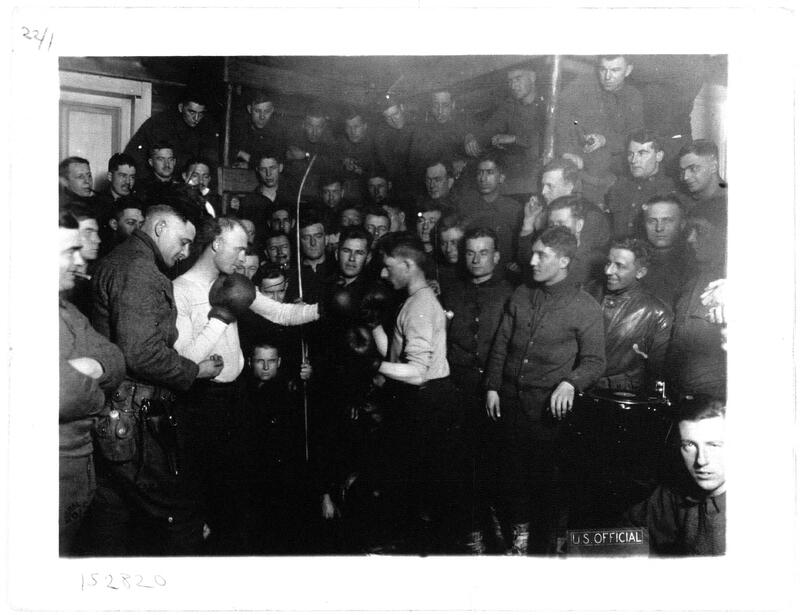

Between the grueling cold and constant threat of attack, boredom was inevitably prevalent for the soldiers of the Polar Bear Expedition. Days stretched into weeks with little change in routine amidst the homogenizing snow, driving men to seek out moments of relief where they could. They turned to simple activities to fill the time, ranging from boxing to ice skating, in attempts to bring brief distraction from the isolation of their mission. These moments of recreation provided more than just entertainment—they were a vital break from the psychological strain of a conflict that felt as endless as the frozen landscape around them.

Two months after the start of the Polar Bear Expedition, the Armistice of 11 November 1918 was signed, marking the end of armed conflict. As the world cautiously rejoiced, Russia remained in political turmoil, and the men of the Polar Bear Expedition remained entrenched in the uninviting snow of Achangel. Over 200 American soldiers died during the campaign in northern Russia, their sacrifices largely overshadowed by the end of what came to be known as the Great War. These men faced not only enemy fire from Bolshevik partisans they found themselves fightiing, but also the brutal Russian winter, where subzero temperatures, frostbite, and disease claimed lives as efficiently as any weapon. Far from the well-defined trenches of France, the soldiers fought in scattered skirmishes, ambushes, and nighttime raids that made death feel sudden and arbitrary.

While World War I’s losses were viewed as part of a shared, global sacrifice, the deaths of the Polar Bear soldiers were harder to place. Their mission was not framed as part of a world-historical moment but as an aftershock of it. And in historical memory, that distinction matters. The dead of the Western Front can be argued as unavoidable within the context of it being inetvitable. The deaths in northern Russia, by contrast, were harder to justify. Soldiers, families, and even military officials questioned the purpose of the expedition, even leading to a mutiny. When the surviving Polar Bears were finally able to return home in 1919, many of the dead had to be left behind, unable to be recovered for decades due to American-Soviet tension. Their war had not been won, nor had it been neatly concluded. Expecting to fight Germans, just to find themselves in the midst of the perpetual political strife that defines the Russian Empire, the soldiers of the Polar Bear Expedition's sacrifices were buried in snow.