About Our Archive / Project Description

Welcome to Creative Media of Alternative Political Movements in Southeast Michigan.

This is an online archive centered on the creative media that was produced by and in response to alternative political movements in Michigan. We define an "alternative political movement" as any movement that goes against the political status quo.

Documentary Focus

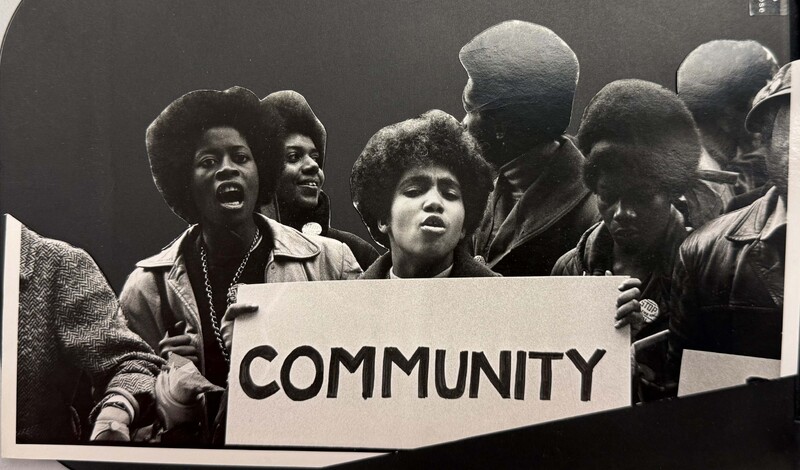

The documentary focus of this online archive is creative media from alternative political movements in Southeast Michigan during the second half of the twentieth-century. Here, “creative media” can be defined as any work involving an imaginative and/or artistic expression of an idea. Examples of creative media include paintings, posters, photographs, zines, poetry, music, literature, and so on. “Alternative political movements” that this archive focuses on are those which fought for social justice issues, as well as often challenged the government and those who held societal power. As a result, this archive offers a bottom-up view by collecting, describing, and presenting records from these groups, highlighting not only their contributions to community and politics but also sometimes their exclusion from traditional archives in institutional settings.

Our Audience

The primary users of this archive would be activists, as our collection attempts to document and describe previous social and political movements, which are also generally underrepresented in traditional archival institutions. Not only could archivists learn from these movements, perhaps even finding inspiration in their artwork, music, programs, and more, but they can connect with them over shared values and goals. Given history is cyclical, current activists might apply past methods of outreach to today's landscape. Scholars Wakimoto et al. (2013) emphasize the connection between archival practices and activism when archivists “acknowledge, embrace, and include multiplicity of voices and competing narratives in the archives” to combat silences (p. 295). As a result, activists could utilize this archive to establish a collective memory, fight against historical erasure, and correct historical absence. In essence, the archive could be a tool to provide a sense of legitimacy for those both in the past and present.

Activists might be academics, while some might be part of the general public. However, activists often do not see themselves as adequately represented in the archives. These users, then, might not have a strong background in archival knowledge and could even be considered skimmers. Scholars Smith and Villata (2020) identified less than 0.1 percent of archival users as “deep divers” compared to the 98 percent who are “skimmers” (p. 244). Activists, depending on their backgrounds, could fall between these categories, but most would likely benefit from an intuitive layout and thoughtful metadata. The phrase “thoughtful metadata” refers to metadata that reflects the ways in which these activists describe themselves and are not biased against their movements, as activists might be distrustful of larger institutions who could censor materials. Furthermore, since many materials from alternative political movements are ephemeral, like zines and posters, they might have been excluded from traditional archives. Therefore, our archive strives to collect and describe such records to capture the efforts of the groups represented.

Many secondary users also exist: political and/or cultural historians, students, student organizations and advocacy groups, artists, and members from the general public, particularly those who share an element of their identities or beliefs with those represented in our archive. The engaging and participatory nature of this online archive, with collaborative features like the "Contribute" and "Discover" pages, should encourage users from the general public to enjoy these materials without requiring in-depth archival knowledge.

Consideration of Archival Concepts and Practices

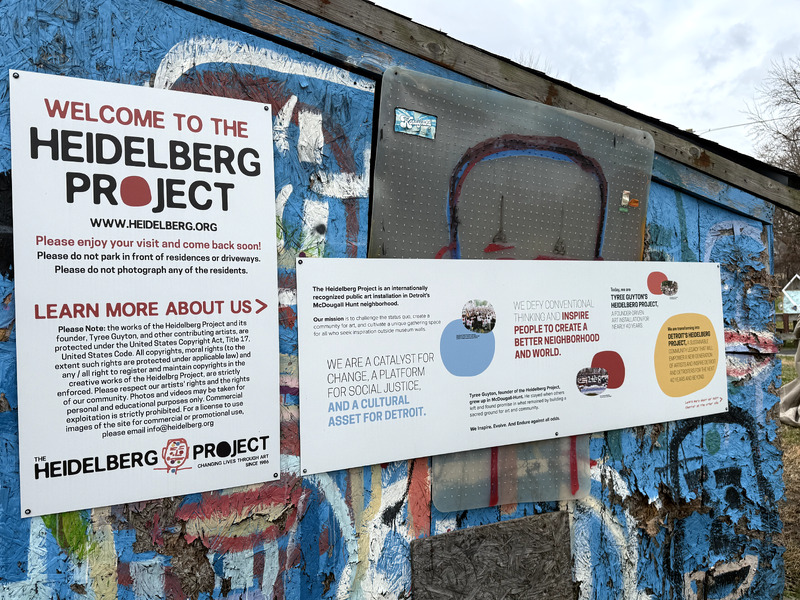

In the acquisition of some materials, our team visited the places where the materials are located. For example, we traveled to Detroit to take photographs of artwork from the Heidelberg Project. As exemplified in the community archive paradigm notably described by Terry Cook, archivists can identify documentary gaps and silences and then seek to address them: a strategy often employed to document the underrepresented, misrepresented, and silenced (Foscarini, 2017, p. 124). Given some of the materials in this archive, specifically the photographs of the Heidelberg Project, are ephemeral and ever-changing, our participation in the acquisition process aims to capture these works at particular moments in time. We also recorded some of the materials’ other features, such as the backs of photographs, and decided to include them in the archive during the appraisal stage. Some of these photographs had annotations that not only offered more contextual information about the record but also revealed the human labor and creativity involved in the original creation of these records, including other contributors to the work. Thus, we deemed them to be significant properties, which are characteristics considered essential for a resource’s usability and/or accessibility (Becker, 2018, p. 15). Such decisions aimed to present a more complete picture of the people involved in producing this creative media.

When it comes to description, our archive focuses less on providing very detailed metadata for each item; many records are ephemeral with unknown creators, like in the case of the Heidelberg Project. As a result, we instead followed scholars Greene and Meissner’s (2005) recommendation of “more product, less process” in which we prioritized making records accessible to more people rather than prioritizing minor details in description and preservation (p. 254). Our team recognizes, however, that we still wrote metadata on the item-level, not fully aligning with Greene and Meissner's vision. We included less description and narrative to allow the items to speak for themselves, centering the voices and visions of these creators over our own. Despite this intention, our team recognizes how biases shape any and all descriptions, considering “[personal] histories, institutional cultures, gender dynamics, class relations, and many other dimensions of meaning-construction are always already at play in processes of records description” (Duff & Harris, 2002, p. 275). Our team, then, acknowledges that our archive still presents a particular story of these records that might not necessarily align with the creators’ perspectives (Duff & Harris, 2002, p. 276). To acknowledge our potential biases, our team wrote positionality statements that can be found on the "Authors" page.

For outreach, our website attempts to encourage user engagement. The "Discover" page, for example, generates random items when refreshed to expose users to more records that are available to them through our website. To avoid labeling items with subject headings, which would only provide our perspective on the materials, we invite users to submit their own tags and requests for future collections. User-created descriptions, such as tags, could encourage interactions between users and archivists while also functioning as a type of public programming (McCausland, 2017, p. 238). Our team engaged with the materials, as well. For instance, we presented the collages of photographs we took of the Heidelberg Project to demonstrate how artwork can continue to inspire new creative expressions and interpretations.

Criteria for Record Selection

The majority of the website’s archival materials comes from the University of Michigan’s Bentley Historical Library, specifically their John and Leni Sinclair papers, and the Heidelberg Project in Detroit. The University of Michigan’s Museum of Art also holds pieces from the Heidelberg Project. When locating these materials, our team prioritized going into the community and interacting with the physical items before digitizing them. When selecting materials, we aimed to collect a wide range of creative media types: photographs, music, posters, writing, and so on. Some of the items we excluded were ones that did not have a direct link to a particular alternative political movement, even if they did include creative media. For instance, photographs of performers at the drums from the John and Leni Sinclair papers were left out of the online archive because our team could not discern what political idea or belief they expressed. Due to our focus on “more product, less process,” our website includes a large number of records. In regards to pieces from the Heidelberg Project, our team followed a more conceptual understanding of the term “item.” The Heidelberg Project is ever-changing with new pieces being added or rearranged, so the “items” themselves are not easily distinguishable. Is one clock a different item from the clock next to it? Is each sign its own item? These were questions we considered during our appraisal process. Rather than separate pieces in an arbitrary manner, we organized them conceptually. For example, pieces might fall under the theme of “time” or “the news.” If they are captured in the same photograph, they become part of the same item. When it came to items from the Bentley, we used the folders already created by their archivists to guide the organization of our collections.

Perspectives

This online archive shares perspectives of members from these alternative political movements, like the Black Panther Party, White Panther Party, and more. Their perspectives are expressed through “creative media,” which is any imaginative or artistic work. Perspectives are also expressed in the annotations on photographs and documents; these annotations provide more information on elements like the creator(s) and people depicted in the records. However, our team did not have the ability nor time to talk to local activists, meaning our team’s perspective permeates throughout the website in the way we format, describe, and present the materials. Part of the reason why we encourage user engagement and collaboration in the website is precisely because we did not talk to local activists, even though they are one of our primary user groups. The perspectives missing from the archive are government employees or those who held more societal power, as well. Their presence can still be felt in the records collected here, as these activists fought against injustice, authority, and spying, but the perspectives from the “top” are intentionally excluded in favor of highlighting the voices historically deemed from the “bottom.”