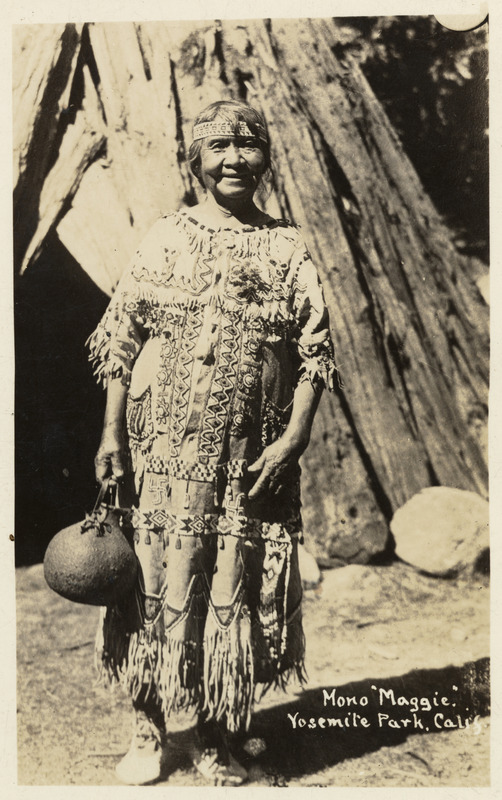

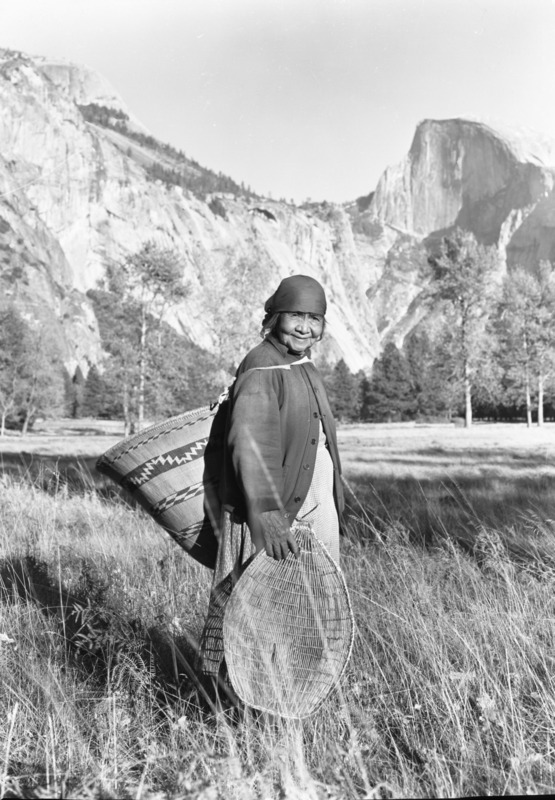

Tabuce "Maggie" Howard

Tabuce “Maggie” Howard (1870-1947) was a Paiute basket weaver, artist, museum docent, and educator. Born near Bridgeport, California, she moved to Mono Lake with her father after her mother’s death. Every year, she and her family traveled to Yosemite to collect acorns and trade with other indigenous groups in the area. Her more permanent stay in Yosemite began when she arrived for medical treatment following a serious accident in which her niece was killed and she was seriously injured. As a result of the severity of her injuries, she chose to stay in Yosemite.

Although she began as a cook and housekeeper for residents of the area, in 1929, Tabuce Howard became Yosemite’s first museum docent. Yosemite had recently transitioned from a state park to a national one, and the involvement of the National Park Service and various collectors created increased interest in indigenous ways of life and basket weaving in particular. At the Museum Camp, she demonstrated ways of life that were central to local indigenous peoples, including how to make acorn meal and weave baskets.

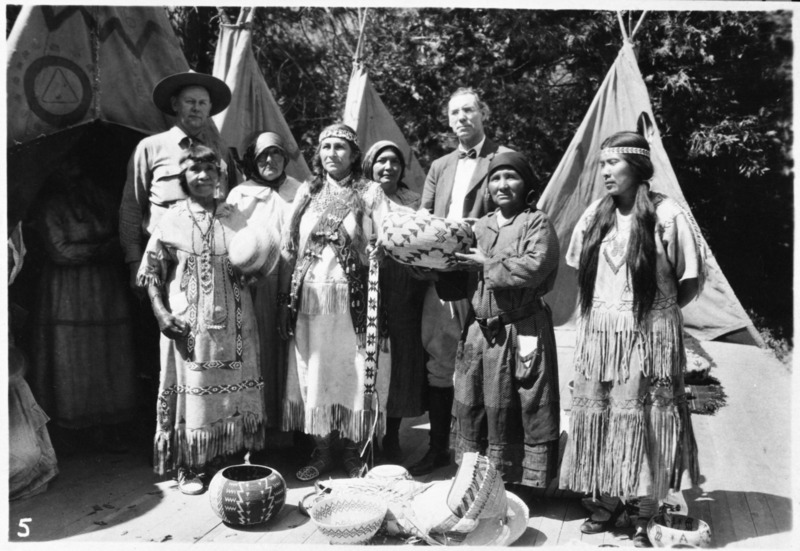

She sold her work to collectors and visitors and also entered many baskets into the competitions held during Indian Field Days. Indian Field Days were incredibly problematic events in which Ahwahneechees were paid to wear costumes belonging to Plains Indians, and while they were eventually condemned, they were crucial places for basket weavers, mostly women like Tabuce Howard, Lucy Telles, and Carrie Bethel, to make a name for themselves with collectors and generate a livelihood off of their work.

Tabuce Howard’s work also showed her own unique approach to beading and weaving. She sometimes included her name in basket weavings and would stitch a pattern onto her weaving prior to beading so she could work off of a pattern rather than counting her beads individually. In 1942, Tabuce Howard returned to Mono Lake to live closer to her son until she died five years later. Her work is still remembered in the parks today, as her baskets were part of the Yosemite National Park Museum’s exhibits on basketry, which you can still see in their virtual museum exhibits online. Yosemite has used images of Tabuce in a couple of social media posts as well, highlighting her work as “an unpaid interpreter of her own culture for over 20 years” who introduced “thousands of tourists to the cultural heritage of the land they were visiting." Her work in the park is still felt and acts as a powerful reminder of the necessity of prioritizing indigenous voices as we approach issues facing the national parks today.