Folklore in Cuba

In the 1930s, Fernando Ortiz sponsored the first public performances of Afrocuban religious music in Cuba. He had been writing about Afrocuban expressive traditions for several decades, but this was a shift in his intellectual orientation from a criminological perspective in his first book La Hampa Afrocubana to a more anthropological orientation in his subsequent publications. He is considered the father of Afrocuban studies and his contribution to the field is the concept of transculturaltion. This concept describes a process by which ancestral cultures blend producing a mutually transformative effect. It countered prevailing attitudes about the dynamics between European settler cultures and Afrdescendent or Indigenous cultures which were thought to be subordinate and expected to assimmilate or acculturte to the European dominant social paradigms. This was a breakthrough in understanding the cultural patterns of the Americas. Despite much criticism the concept endured. Influential indefining national culture in Cuba and redefining Cubanness or cubanidad as a mixture of Hispanic and African heritaage transculturalation was part of a larger discourse in Latin America, known as mestizaje or mixture. The notion of mestizaje was key emerging nationalist movement as countries sought to incorporate marginalized Indigenous and Afrodescendent communities into legitimate modern nations. In Cuba this liberal movement was called Afrcubanismo or Afrocubanism. The writings of Ortiz and his contemporaries influenced a broad literary, social, and artistic movement.

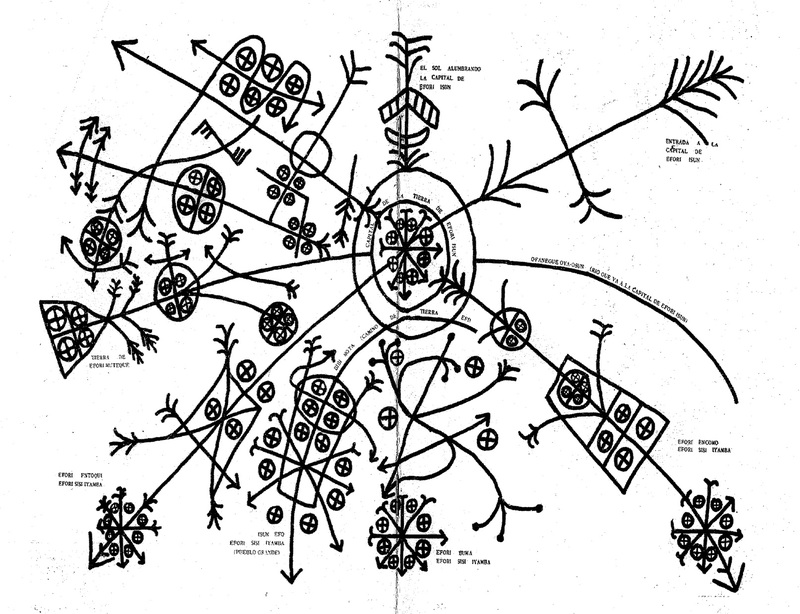

Immediately following the Cuban Revolution (1959), Afrocubanism again became an important means of defining the nation. Prominence given to public performances of Afrocuban religious music signaled the radical social change that the new government, led by Fidel Castro’s July 26 movement, sought to establish. A series of concerts produced by musicologist and composer, Argeliers León, head of the music department of the newly formed National Theater of Cuba (June 1959), staged Afro-Cuban religious traditions in major concert venues. Such venues had previously been reserved for classical music, but moreover, prior to the Revolution it had been unthinkable to present traditional Afrocuban drumming, much less religious music on a concert stage. A student of Ortiz, León staged the concerts in a manner seeking to project ethnographic authenticity as well as the purity of the tradition. The cover of one of the concert programs features the symbolic graphic designs (anaforuana) of the Abakuá brotherhood. (Reproduced here for a concert in 2011 at Casa de Africa in Havana).

Cultural development was a major part of the socialist government's priorities. Rogelio Martínez Furé, who had been a student of Argeliers Léon, also worked extending the tradition of Ortiz by fostering research and public presentation of Afrocuban religious music. Furé along with Mexican choreographer Rodolfo Reyes founded the National Folkloric Ensemble of Cuba (CFNC) in 1962. The CFNC blended modern dance, elements of drama and theater technique, ethnographic research, and traditional music and dance to develop a new performance genre. Folkloric shows or espectáculos folklóricos became a prevasive form of public entertainment and education about Afrocuban and popular traditions on the island.

Folkloric shows are a secular and highly stylized representation of religious music and dance and popular traditions. The founding generation of the CFNC consisted of performers drawn from the living tradition, that is to say from the communities that practices the Afrodescendent religions in Cuba. Performers like, Nieves Fresenda, Trinidad Torrega and others worked with choreographers and costume designers to develop complex stage shows with elements of ethnographically accurate performance. The music perhaps more than the dance remained closer to the living tradition, and even so there were transformations and exceptions mand in translating it to the stage. Despite the interest in ethnographic accuracy, there was an equal interest in producing high quality artistic dance. For many years, only highly trained dancers from Cuba's conservatories were able to be placed in elite performing groups like the CFNC.

The image of Furé at left is a page taken from the CFNC program book published in 1963. It contains images of the costume design, religious objects, performances, and portraits of the performers. Among those are the youthful visages of musicians and dancers who went on to illustrious careers and to become legends of Afrocuban folkre over the following decades. Many are the founders or directors of contemporary ensembles.

The repertoire of the CFNC represnets the different expressive traditions joined under the singular category of Afrocuban folklore. Most of what is referred to as folklore in the Ortizian tradition of scholarship is religious music and dance. Subsequent generations added secular traditions to this category. The religious traditions are identified with particular ethnic or language groups: Lucumí/Yoruba, Congo/Bantú, Carabalí/Abakuá, Arará and Iyesá/Fon and Ewe. Scholars disagree about the meaning of the ethnic designations, with some drawing more direct parallels to African ethnicities and others arguing that the social conditions of ninetheenth-century Cuba fostered the foundation of ethnically mixed cabildos, or mutual-aid organizations leading to ethnically mixed groups that based identity on initiation. Cabildos were run by free Africans and these organizations provided support to individuals that mitigated some of the horrors of slavery. The cabildos were key in establishing African religions, music, dance, and language in Cuba. The repeortoire of the CFNC also included popular traditions rooted in Afrocuban music such as comparas, congas, and rumba, and salon dance traditions like contradanza and danzón. The choreography depicted in the poster is from the Ciclo Congo.

Folklore has been directed to domestic and foreign audiences alike. Within Cuba, folkloric performances are presetned at official events, for popular entertainment in weely live events known as peñas. Folklore is also features in large theatrical venues and in festivals. During the 1990s, there was a deep economic crisis in Cuba and after decades of eschewing tourism due to its associations with corruption amd commercialism, Cuba developed the tourism sector in order to get access to much needed hard currency. Folklore and popular dance music were in the forefront of the development of cultural tourism.

Through the development of a conservatory program in folkloric dance and emphasis on the production of a repertoire of set pieces, the CFNC began touring internationally shortly after its founding. Their program contained some of the most compelling dance shows in the modern repoertoire. Repertoire was shaped in accord with categories and tropes established by Ortiz and his students. This means that the traditions were interpreted in the context of national culture, which highlighted some themes and downplayed others. Furthermore, some religious communities tended to share their esoteric knowledge more freely than others and the folkloric representations were different because of that. Of coruse, audiences who did not know the ritual styles of music and dance could not detect the differences, but adherents to the traditions could. This was especially the case with the Abakuá community, whcih tended to limit sharing of their traditions and pushed back against some folkloric represenations. The repertoire of the CFNC was ennumertated and describes in a 1977 catalog. It includes set-pieces from three of the African ethnic groups outlined as the main contributors to Cuban culture: Yoruba, Congo, and Abakuá were represented in the early development of the core repertoire. The Ciclo Yoruba was based on the personification of Yoruba orishas (Yoruba deities). The Ciclo Congo was based on narratives and dramatizations weaving together ritual, dance and history. The Ciclo Abakuá was based on different parts of the ritual known as the plante, or annual ritual celebration. The Abakuá folklore performance, however, did not become a major part of the repertoire and by the mid 1980s can be seen only in pieces that compiled many folkloric rhythms such as the Concierto de Percusión (1986). In addition to representations of Afrocuban religious practices, repertoire included presentations that celebrated the quotidian lives of working-class people and historical salon dances. The former was presented in choreographies of the pregón (street vendor’s calls), rumba, a festive, recreational genre, as well as popular and social dances, and comparsas and congas of carnival (Martínez Furé 1963, 1977).

Following the Revolution, cultural production became a priority in Cuba under socialism. This goal included the development of cultural forms unique to the country and which celebrated the working class. The dvelopment of folkloric shows (espectáculos folklóricos) as a mode of public entertainment and education was just one of the cultural expressions that drew on Afrocuban religious music and dance. Cuban modern dance was another form of culture developed after the Revolution, which also drew on folklore. The modern dance company, Conjunto de Danza Contemporaneo de Cuba, founded and led by Ramiro Gurerra, worked with drummers and dancers from the Afrocuban religious communities alongside modern dancers from the US and other countries. The collaboration, directed by Guerra, led to a uniquely Cuban style of modern dance. Jesús Pérez (Oba Ilú, as he was known in the Yoruba/Lucumí religious community) was the main drummer for the Danza Contemporanea company. Pérez went on to make recordings of Afrocuban religious music from the Yoruba/Lucumí tradition. He is shown holding one of the drums fromt he Yoruba/Lucimí batá ensemble. He passed away in 1985 and is memorialized by the use of his Lucumí name for the ensemble founded and led by Gregorio Hernández.