Black Bottom and Paradise Valley were the epicenter of black life in Detroit from the 1930s-1960s. These neighborhoods don’t exist anymore. There is now a move to bring them back, in a new format. - Ken Coleman, Detroit Is It

Paradise Valley

PARADISE VALLEY WAS THE BUSINESS DISTRICT AND ENTERTAINMENT CENTER OF A DENSELY-POPULATED AFRICAN-AMERICAN RESIDENTIAL AREA IN DETROIT – KNOWN AS BLACK BOTTOM – FROM THE 1920’S THROUGH THE 1950’S.

During the 1920’s, the black population in Detroit swelled from 41,000 to 120,000 as new migrants from the South arrived daily to seek employment in the automobile industry. The cramped near east side neighborhood of Black Bottom was one of the very few areas blacks were allowed to reside. The residents’ daily needs were amply met by more than 300 black-owned businesses in Paradise Valley, ranging from drugstores, beauty salons and restaurants to places of leisure such as nightclubs, bowling alleys with bars, theaters and mini-golf courses. Paradise Valley History

The Valley was located near the downtown area and the marker commemorating its existence is located on St. Antoine near Beacon Street—not far from what is currently Ford Field. The marker notes that during its height, Paradise Valley was an extraordinary community that is only rivaled by the Harlem Renaissance.Black Bottom Archives

Beginning in the 1940s, urban renewal projects, the construction of freeways, and new development devastated African American neighborhoods, including Paradise Valley. The valley’s last three structures, located along St. Antoine Street, were demolished in 2001. Paradise Valley Historical Marker.

Near Paradise Valley is the marker commemorating St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church which was instrumental in the Underground Railroad and is where the Detroit branch of the NAACP was organized.

Black Bottom

Black Bottom was a predominantly Black neighborhood in Detroit. However, some historians believe that the name of the neighborhood predates its most well-known residents and may be derived from the rich, black soil where Indigenous people and French settlers farmed a variety of crops. (Coleman, 2017)

Between World Wars I and II it became home to thousands of African Americans who migrated from the South in search of a better future offered by factory work. Housing discrimination forced them into neighborhoods like Black Bottom. They paid overpriced rent and often packed multiple families into single homes as they built a new community. Those who grew up in Black Bottom included Coleman A. young, Detroit's first black mayor; Joe Louis, the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1937 to 1949; and Ralph Bunche, the first black recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, honored in 1950 for his role as a mediator with the United Nations.

Due to segregation, the neighborhood was mostly socially and economically independent, Black-owned enterprises, such as grocery stores, restaurants, and shops, occupied its street corners and the business district along Hastings Street. Churches and schools provided residents with social spaces and a sense of belonging. In the 1950s-60s, the Detroit government razed most of Black Bottom as part of its urban renewal and "slum clearance" plan. Lafayette Park and Chrysler Freeway (I-375) replaced the community. Many families were displaced and given no resources for relocation. They retained their connections to each other through several Black Bottom churches that endured into the twenty-first century. Black Bottom Historical Marker

In 2020, a new marker on East Lafayette Boulevard was erected to commemorate the site and many notable Detroiters who lived there. Including Coleman Young, Detroit’s first Black mayor; legendary boxing champion Joe Louis, and Ralph Bunche, the first Black recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. Other markers near the neighborhood include the Fannie Richards Homesite erected in honor of Detroit’s first Black public school teacher. An innovative teacher, Fannie Richards was instrumental in the integration of schools in the state and she taught the city’s first kindergarten class. Visit Detroit

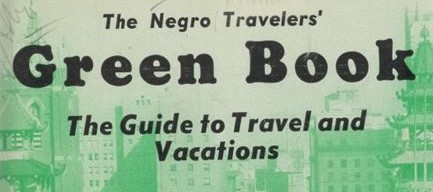

Not surprisingly, the Green Book locations match exactly with areas of Detroit with more Black residents (due to restrictive and discriminatory housing policies). For more information on discriminatory housing practices in Detroit, visit Detroitology's Detroit Redlining Map 1939.

Gentrification & Urban Renewal

We want to hold space to acknowledge the fact that many of the Green Book listings included in this archive were effected by gentrification and urban renewal. The Urban Displacement Project defines gentrification as, "a process of neighborhood change that includes economic change in a historically disinvested neighborhood —by means of real estate investment and new higher-income residents moving in – as well as demographic change – not only in terms of income level, but also in terms of changes in the education level or racial make-up of residents." The Inclusive Historian’s Handbook provides information about urban renewal here: "Urban renewal is the process of seizing and demolishing large swaths of private and public property for the purpose of modernizing and improving aging infrastructure. Between 1949 and 1974, the U.S. government underwrote this process through a Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grant and loan program. Although the money was federal, renewal plans originated with and were implemented at the local level.

In cities nationwide, the consequences of urban renewal included the destruction of historic structures, the displacement of low-income families, and the removal (often closure) of small businesses. The local officials and business leaders who promoted renewal regarded the federal program as the best available method for addressing the problems attendant with suburbanization, a process fueled by HUD and G.I. Bill mortgages. For many black, Latinx, and low-income families, however, it was a tragedy and injustice, a loss of home and community. Urban renewal reshaped the geography and demographics of cities, and, in the process, exacerbated conflict and promoted resistance." (Urban Renewal – The Inclusive Historian's Handbook)

Both of these systematic and institutionalized practices have disenfranchised historically Black communities across the country including places like Oakland, CA and Harlem, New York. We encourage our users to keep the Black Bottoms and Paradise Valley communities in mind when you visit Detroit. Using our digital archive, you’ll also have the opportunity to virtually see how the area has changed from what it was to how it looks now.

Paradise Reclaimed

In 2016 the Downtown Development Authority of the City of Detroit approved a comprehensive plan to redevelop nine properties near the old Paradise Valley area culminating in a $52.4 million investment in construction and renovations. Newly named Paradise Valley Cultural & Entertainment District project includes a development called Hastings Place, after Hastings St the bustling business district of Paradise Valley. This $27 mission, 83,340 sq. ft. building will include 60 apartments, a five-story parking deck, retail spaces, and new offices for the Michigan Chronicle. Detroit Metro Times

For more information on the Paradise Valley Cultural & Entertainment District project, see Detroit Paradise Valley