Historical Timeline

For more information on early Black communities in Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti, please visit:

- Ann Arbor District Library’s (AADL) map of African American Historical Sites

- The African American Cultural and Historical Museum of Washtenaw County’s Walking Tour of Ann Arbor

- Washtenaw County’s 2017 Report on Housing.

Washtenaw Urban County, & Ann Arbor Housing Commission. (2017). 2017 Washtenaw Urban County Assessment of Fair Housing. https://www.washtenaw.org/DocumentCenter/View/2333/2017-Washtenaw-County-AFH-Plan-PDF

Justice InDeed. (n.d.). Mapping. Justice InDeed. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.justiceindeedmi.org/mapping

The Federal Housing Association’s national appraisal system is used to determine the “financial risk” of purchasing property in cities across the U.S (Herbes-Sommers et al., 2003). This appraisal system came to be known as “redlining,” named after the color that indicated “high-risk” residential areas on a map that tended to have high concentrations of people of color (Herbes-Sommers et al., 2003). Green was used to indicate a high rating and low investing risk, while “communities that were all minority, or in the process of changing, got the lowest rating and the color red” (Herbes-Sommers et al., 2003, 33:40) (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, n.d.).

Unlike nearby Detroit, Washtenaw County did not enact redlining, with racially-restrictive housing covenants (see Glossary item for this term) being the most common form of housing discrimination in the area beginning in the 1910s (Washtenaw Urban County & Ann Arbor Housing Commission, 2017)(Justice InDeed, n.d.).

Herbes-Sommers, C. Cheng, J. Adelman, L. Smith, L. Strain, T. (Director). (2003). Race - The Power of an Illusion [Video file]. California Newsreel. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from Kanopy.

Justice InDeed. (n.d.). Mapping. Justice InDeed. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.justiceindeedmi.org/mapping

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (n.d.). Federal Housing Administration. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/housing/fhahistory

Washtenaw Urban County, & Ann Arbor Housing Commission. (2017). 2017 Washtenaw Urban County Assessment of Fair Housing. https://www.washtenaw.org/DocumentCenter/View/2333/2017-Washtenaw-County-AFH-Plan-PDF

The GI bill passed by the Federal Housing Act in 1944 allowed thousands of returning World War II veterans to afford single-family houses, leading to the development of “suburbs” -- “outlying parts of a city” that were outside of a city’s commercial hub and “typically residential in nature” (National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.) (OED Online, 2021). However, several of the residential neighborhoods developed during this time used racially-restrictive housing covenants to prohibit Black people from living in individual properties or even entire housing subdivisions (Justice InDeed, n.d.). These restrictions facilitated the “racial suburbanization” of the United States throughout the mid-20th century (Herbes-Sommers et al., 2003, 34:09).

Herbes-Sommers, C. Cheng, J. Adelman, L. Smith, L. Strain, T. (Director). (2003). Race - The Power of an Illusion [Video file]. California Newsreel. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from Kanopy.

Justice InDeed. (n.d.). Mapping. Justice InDeed. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.justiceindeedmi.org/mapping

National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (1944). Our Documents: 100 Milestone Documents from the National Archives. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=76.

OED Online. (2021). suburb, n. Oxford University Press. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

“The FHA underwriters warned that the presence of even one of two nonwhite families could undermine real estate values in the new suburbs. These government guidelines were widely adopted by private industry.” (Herbes-Sommers et al., 2003, 32:45).

Justice InDeed. (n.d.). Mapping. Justice InDeed. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.justiceindeedmi.org/mapping

You can learn more about the families displaced by urban renewal from 1950-1966 at Renewing Inequality (Renewing Inequality, n.d.).

Renewing Inequality. (n.d.). Family Displacements through Urban Renewal, 1950-1966. Retrieved December 6, 2021 from https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/renewal/#view=0/0/1&viz=cartogram

PBS Kids. (n.d.). Slum Clearance. PBS Kids: Learning Adventures in Citizenship. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/newyork/laic/episode7/topic3/e7_t3_s2-sc.html

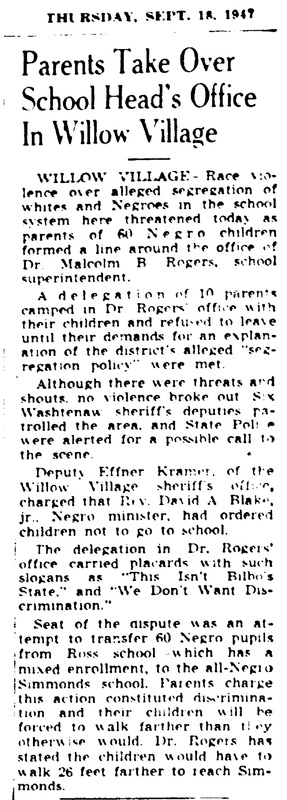

Duignan, B. (2021, November 30). Brown v. Board of Education. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Brown-v-Board-of-Education-of-Topeka/additional-info.

During the summer of 1959, the City Council of Ann Arbor investigated the potential use of federal funding for urban renewal in the city’s North Central neighborhood, ultimately passing a resolution in favor of doing so (“It’s Good-By To ANY Urban Renewal Plan, 7-3”, 1959). However, following a veto by then Mayor Cecil O. Creal and a failed attempt to override it, the City Council shifted its focus towards local implementation (“It’s Good-By To ANY Urban Renewal Plan, 7-3”, 1959). Through its creation of the Neighborhood Improvement Committee in February of 1960, the City Council would begin a process that would enable the destruction of five houses within a year (Ann Arbor City Council, 1960).

Ann Arbor City Council. (1960, February 1). [City Council minute notes]. Bentley Historical Library (Cecil O. Creal papers, Box 7), Ann Arbor, MI, United States.

“It’s Good-By To ANY Urban Renewal Plan, 7-3”. (1959, July 21). Bentley Historical Library (Cecil O. Creal papers, Box 7), Ann Arbor, MI, United States.

For more information on this, check out our section on Sites of Protest in the Mapping Resistance and Community Action gallery.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (n.d.). History of Fair Housing. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/fair_housing_equal_opp/aboutfheo/history.

When nonwhite families started moving to “traditionally white” suburbs after the Civil Rights Act of 1968, the property values of these neighborhoods went down (Herbes-Sommers et al., 2003). Integration and the supposed decrease of property values drove white families out of integrated neighborhoods and into white-only suburbs. When white people left these neighborhoods, property values went down, which subsequently decreased property taxes available for local schools and social services and decreased the resources available to Black families that had just moved in. These deficits in resources would continue in the newly-formed Black communities for several decades (Herbes-Sommers et al., 2003).

Herbes-Sommers, C. Cheng, J. Adelman, L. Smith, L. Strain, T. (Director). (2003). Race - The Power of an Illusion [Video file]. California Newsreel. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from Kanopy.

“Real estate agents preyed on the racial fears of white homeowners to get them to sell their homes quickly for less than market value...it wasn’t African Americans moving in that caused housing values to go down in Roosevelt and other neighborhoods. It was whites leaving" (Herbes-Sommers et al., 2003, 41:11, 43:00-43:13).

In 1974, a controversial Supreme Court case ruled that federal courts had no jurisdiction to enforce the integration of Detroit public schools after massive white flight from the city (State Bar of Michigan, n.d.). This ruling weakened the power of Brown v. Board of Education, providing American public schools a judicial loophole to continue the “de facto” segregation of public schools (see "de facto" in Glossary).

State Bar of Michigan. (n.d.) Michigan Legal Milestones: 36. Milliken v. Bradley. State Bar of Michigan. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.michbar.org/programs/milestone/milestones_milliken-v-bradley