The Politics of Choice: Reproductive Rights in the State of Michigan

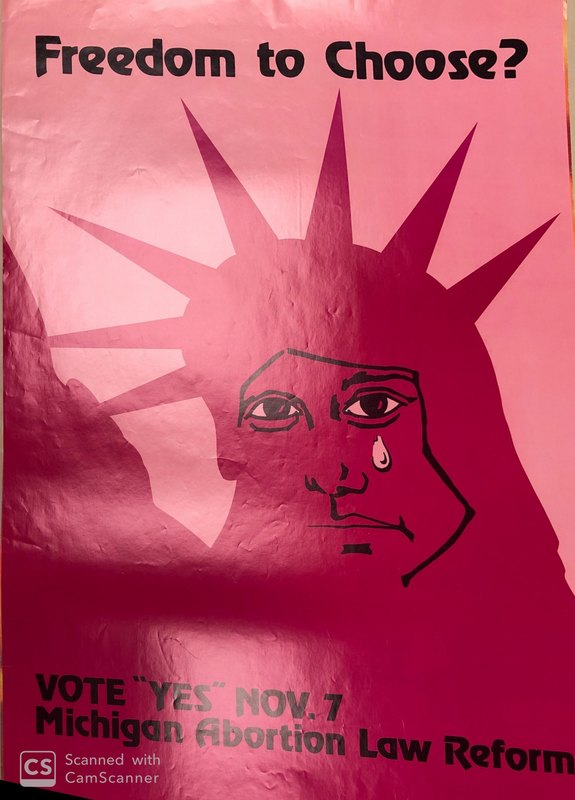

The Michigan Abortion Referendum of 1972: Proposal B

On November 7, 1972 the state of Michigan placed a referendum, known as Proposal B, on the statewide portion of the ballot. The referendum, if passed, would have allowed for licensed physicians to legally perform abortions up to twenty weeks of gestation. The referendum went on the ballot a mere two months shy of the Supreme Court’s decision on Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion during the first trimester nationwide. The fight to get the proposal on the ballot coincided with an election year tinged with racial divisiveness in the state of Michigan, predominately centered around the issues of busing and school integration. “The anti-abortion campaign of 1972 replicated and reinforced the very racial divisions that anti-bussing struggles politicized while deploying similar gendered ideas about mothers and the family” (Frank, 2014). Many of the vocal opponents of the abortion rights referendum were also fierce opponents of busing initiatives, so much so that the two issues were often intertwined and framed as targeted “attacks on children” in the election propaganda that was distributed to constituents in the months preceding the 1972 election (Frank, 2014).

The Michigan Abortion Referendum Committee

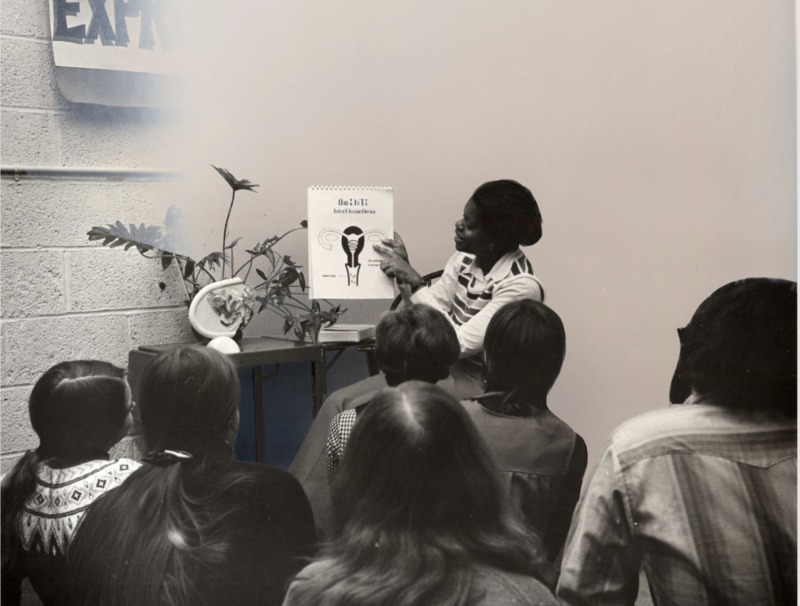

The Michigan Abortion Referendum Committee was formed in 1971 in response to a series of failed and stalled attempts in the Michigan Legislature to ease restrictions on the state’s abortion laws. The formation of the Committee came on the heels of an era in which advertisements were placed in the back of classifieds and college newspapers advertising trips to New York for women in need of options. “Getting to New York was easy — if you could afford it. There was a plane for women who wanted abortions that went from Detroit to Buffalo. The doctors bundled it all together, so the flight was included in the price of the abortion" (Thomson-DeVeaux, 2014). Organizations who served populations that could not afford to fly across the country to obtain a safe abortion performed by a medical professional, such as Planned Parenthood, were legally relegated to providing their clients with "educational tools" that did not include any information regarding access to abortion.

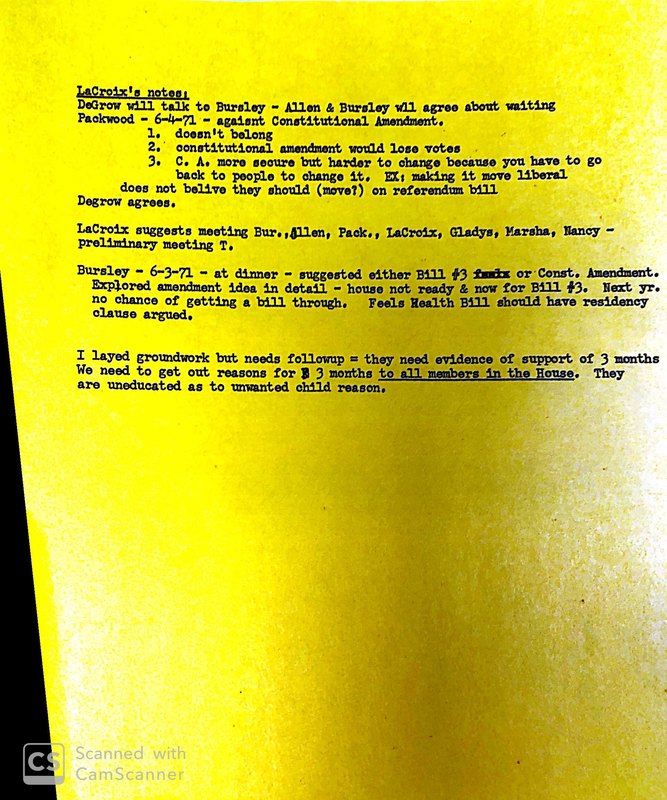

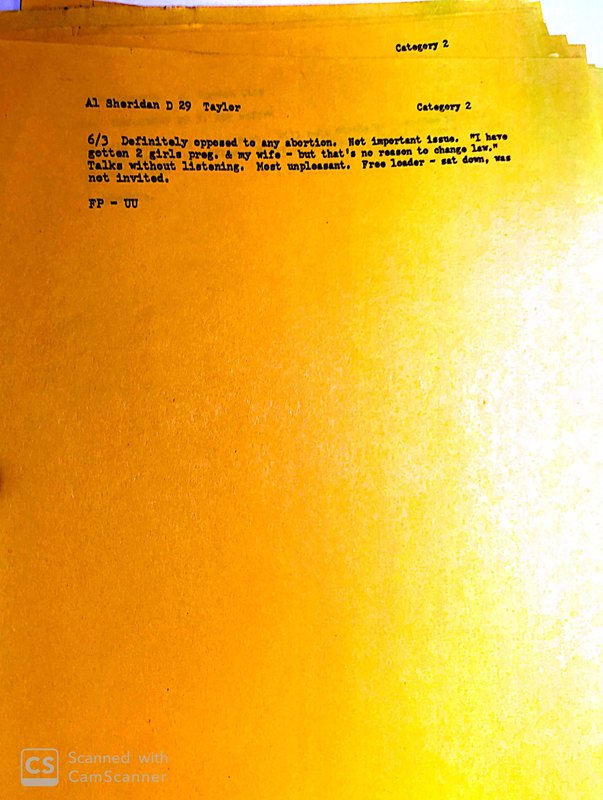

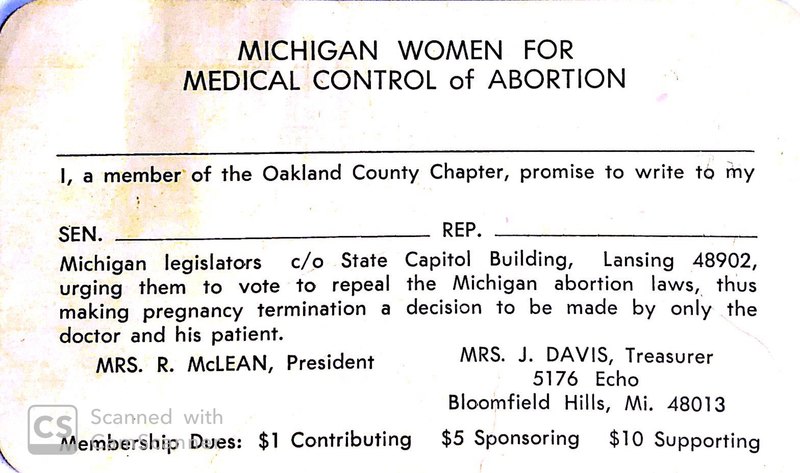

A significant focus of the Committee’s recorded efforts to get the referendum on the ballot were centered on providing evidence to legislators that choice was not a partisan issue, rather a socioeconomic one. The Committee attempted to achieve this through use of a structured letter writing campaign. The campaign was originally organized by Committee members, but it received both local and national press coverage when the Committee was able to attract a notable contingent of bipartisan support from across the state. Many of these supporters in turn wrote letters to their legislators urging them to support the call to place the referendum on the 1972 ballot. Additionally, Committee members personally visited the offices of every single Michigan legislator who held office at the time in effort to both inform legislators of their plight, and to document the legislators’ comments regarding the impending vote on the ballot proposal (Michigan Abortion Referendum Committee Papers, 1972).

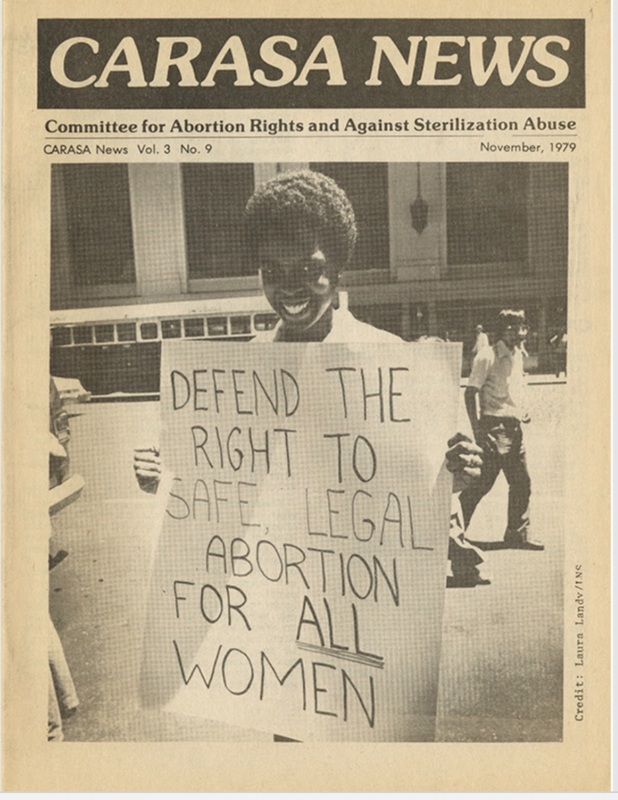

Despite the bipartisan effort, the ballot proposal was ultimately defeated amid outcries that the campaign against the proposal was steeped in racially charged symbolism and utilized tactics of fearmongering. The ruling handed down in Roe v. Wade three months later meant that the state would have to allow licensed physicians to legally perform abortions. However, following the Supreme Court decision, the organizations that originally opposed the proposal in Michigan directed their efforts to the distribution of materials that promoted notions of forced sterilization in the wake of the legalization of abortion. "In the early 1970s, the racialised and gendered battles over abortion reform were articulated through child protection rhetoric and at the expense of women's reproductive choices" (Frank, 2014). Some of the same propaganda materials that were distributed in the 1970s have recently resurfaced on social media sites in the wake of many states passing bills that would either ban or limit the legality of abortion.