Busing and School Desegregation in the 1970s: Detroit, Michigan

School desegregation policies gained momentum at the close of the 1960s when the courts ruled in favor of mandatory busing plans to integrate segregated public school districts (Hilbert, 2018). However, the events of the following decade would carry ramifications for the equal education movement that can still be felt to this day. In the 1970s, policy makers were vocal in their support of an anti-busing legislative agenda, including President Richard Nixon (Hilbert, 2018). Additionally, the courts shifted decidedly away from legal decisions that were beneficial to integration, instead striking down decisions that promised progress (Hilbert, 2018). One of the most influential touchstones was the Supreme Court’s 1974 Milliken v. Bradley decision, a case that held profound implications for the future of school desegregation and integration plans (Hilbert, 2018; Nadworny & Turner, 2019). These combined factors created major setbacks to achieving true educational equality mandated by the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision (Hilbert, 2018).

The School District's Answer to Busing Opposition: Magnet Schools

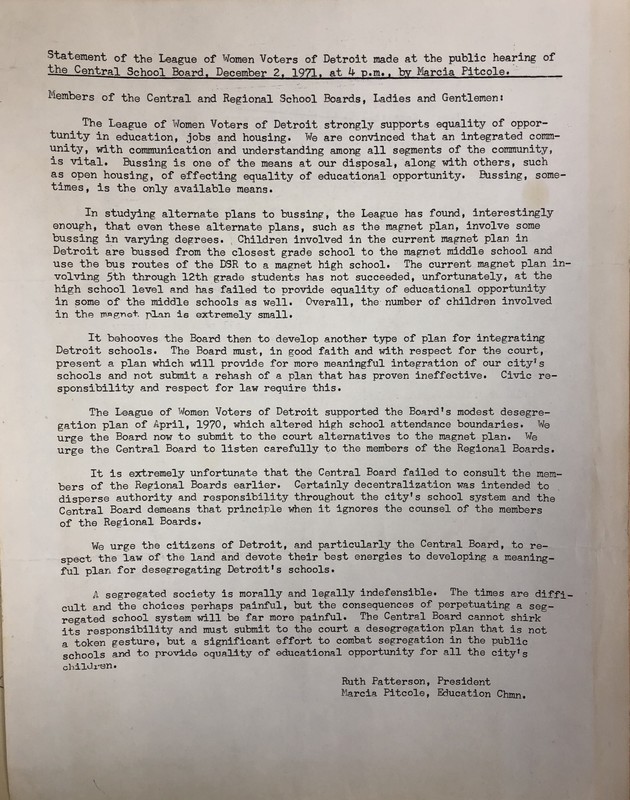

In response to the political climate surrounding the busing issue, school districts turned to the school of choice-based option to desegregate schools – magnet schools. Magnet schools were created with a particular academic or curricular focus to attract students of different racial backgrounds to schools across district lines, both in the suburbs and the city (Hilbert, 2018). However, magnet schools were often ineffective in district-wide efforts of desegregation, and “limited placement options” made them unavailable to many students (Hilbert, 2018, p. 104).

Milliken v. Bradley 1974 Decision

The 1974 Milliken v. Bradley Supreme Court ruling held profound implications for the future of school desegregation and integration plans. In response to a lawsuit against officials from the state of Michigan and the city of Detroit for racist housing policies that essentially prevented African Americans from moving into the suburbs, the Federal District Court and the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ordered the city of Detroit and its suburbs to implement a far-reaching busing plan to desegregate Detroit’s schools (Stevens, 1976; Nadworny & Turner, 2019). The state was investing vast amounts of money into these suburban schools, and then building school district lines around them to prevent black students from attending them (Nadworny & Turner, 2019). The Supreme Court overturned the earlier ruling of the lower courts, arguing it could not be proven that the suburbs had drawn these school district lines with the intent of segregating Detroit’s schools and upheld the argument that the federal government should not take an active role in the administration of local schools (Nadworny & Turner, 2019). This ruling “essentially [prohibited] interdistrict, metropolitan-wide remedies” to segregated schools (Hilbert, 2018, p. 102).

School Desegregation After 1974

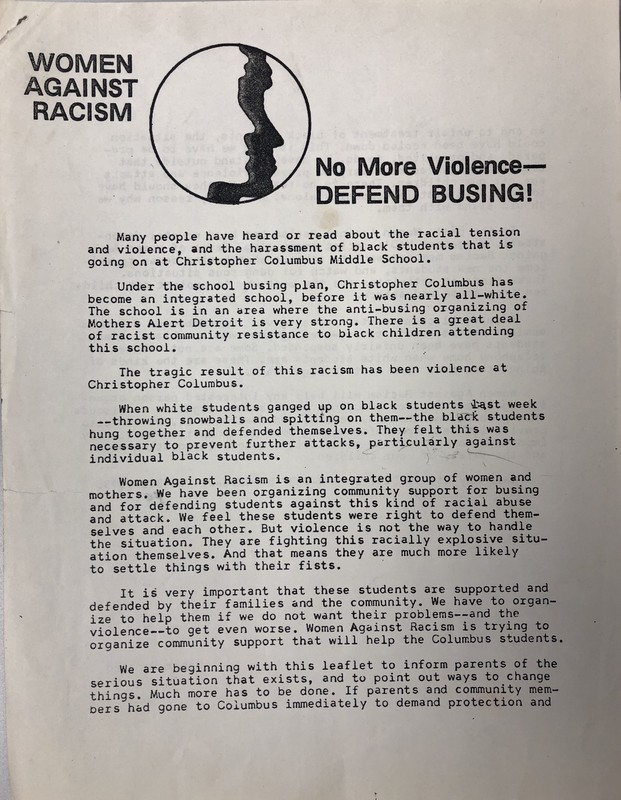

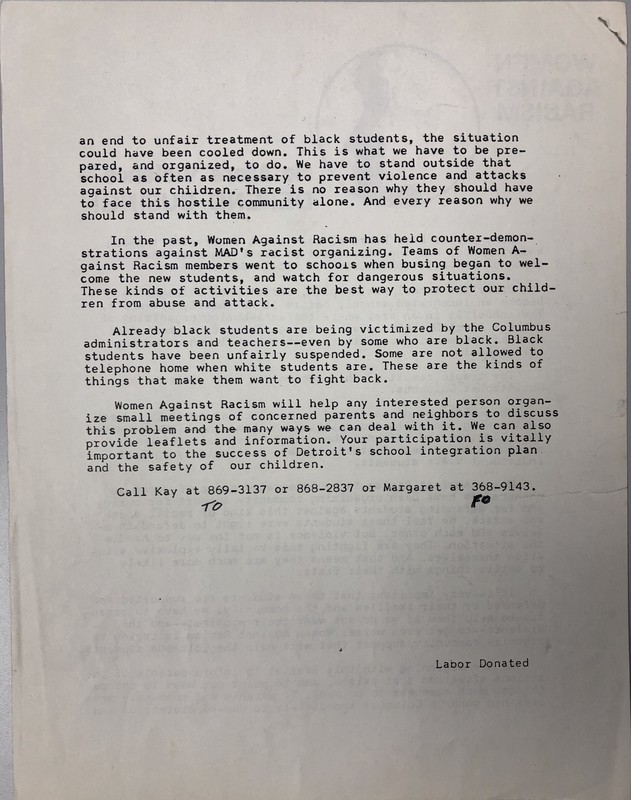

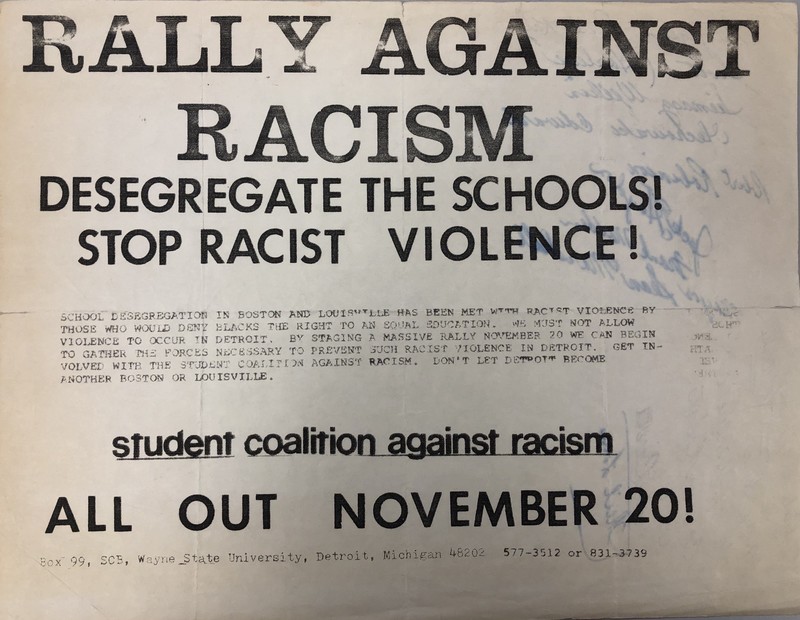

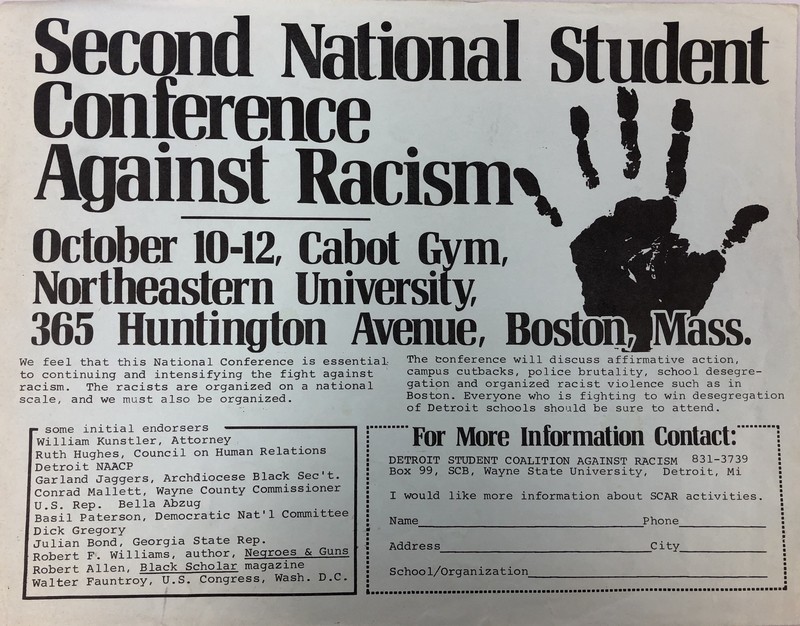

The subsequent busing and desegregation plans were limited in scope. Many civil rights activists in the African American community expressed their concern and anger that these busing plans did not go far enough to achieve true justice and equality (Stevens, 1976). These plans were mostly designed to please white parents, and black students who were transferred to different schools were often bullied (Hilbert, 2018). They focused on sending black students to all-white schools but did not revise school curriculums to be inclusive and representative of a diverse student body, nor did they equally represent the voices of black teachers and administrators (Hilbert, 2018). Additionally, while desegregation plans prioritized having an equal number of students of different races in public schools, they did not address the intersection of housing and education policy (Hilbert, 2018). These plans failed to address discriminatory practices institutionalized in both realms, making it harder to completely eliminate the separate and unequal practices in education systems ruled unconstitutional by Brown v. Board of Education (Hilbert, 2018). Consequentially, the fight for busing and an equal access to education continued through the 1970s and beyond.