Toledo War

Context of Toledo War

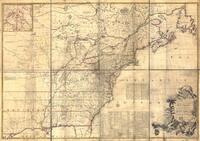

In 1835, Michigan had enough people settled to become a state in accordance with United States federal law, but statehood could not be granted because of a territorial dispute with Ohio over the Toledo Strip. The Toledo Strip stretched along the border of Michigan and Ohio from Lake Erie to Indiana with the city of Toledo inside of it. Ohio claimed the Toledo Strip, despite Michigan officially owning the land. The dispute caused both sides to pass legislation attempting to force the other side's capitulation. Both Ohio's Governor Robert Lucas and Michigan's Stevens Thomas Mason helped make criminal penalties for residents submitting to the opposing state. Militias were deployed for both states near Toledo, but there was hardly any interaction with each other. There was only one single military confrontation which ended without any casualties, with shots simply firing into the air.

In 1836, the House Judiciary Committee investigation reported that Michigan must give up the Toledo Strip to Ohio. In a compromise for losing the Toledo Strip, Michigan in return received what is now the Upper Peninsula. With compromise on the table, the people of Michigan met to discuss it. They held two conferences and in the second conference, Michigan agreed to the compromise with hopes they would be able to refute the ownership of the Toledo Strip. After that agreement, a bill was created in Washington D.C that officially made Michigan a state in the union. While at first, it did not seem to compare with the economic potential Toledo would have brought to Michigan, the Upper Peninsula would prove valuable to Michigan’s economy. By accruing the Upper Peninsula, Michigan acquired 9,000 square miles of unequaled mineral and timber land. This land contained resources that would be important for the lumber companies, and it allowed Michigan to have an impactful mining industry.

Letters to Stevens Thomas Mason, Michigan's Governor

Ceded land to Ohio

Ultimately Toledo went to Ohio, land that originally was inhabited by the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, and sold for less than its value. The Potawatomi tribes were forced west toward Kansas and Oklahoma as a result of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, leaving their original lands near Indiana and Ohio. Today the Citizen Potawatomi Nation is forced to only have rights to lands that are allotted by the government.

Treaty and Letter locations

Search by area in Michigan, and outside the state, to see where treaties and letters were written, signed, and the land they are correlated with.