Racialized Housing

Housing discrimination was a significant issue in California and many other states during the 1900s. California housing discrimination made it so that people of color could only live in certain areas. This is a similar idea to segregation and is often called redlining. This was enforced through a multitude of ways, with the simplest one being the straight discrimination of landlords not allowing people of color to rent or buy housing in the "nicer" areas. Another way to enforce this was through legal documents such as "racial covenants" that stated on the deed to the houses that a Black, Asian, Mexican, or Native person could not live there.

This was the case for so many people of color, and that is why you may have heard of, or seen areas that are referred to as "China town" or "Mexican barrios." Areas with a high concentration of one ethnicity was often due to this housing discrimination. In addition to this, more often than not they were subjected to live in the poorer, low run parts of town that often were not suited for basic human needs. Some homes would be dirty and have no running water.

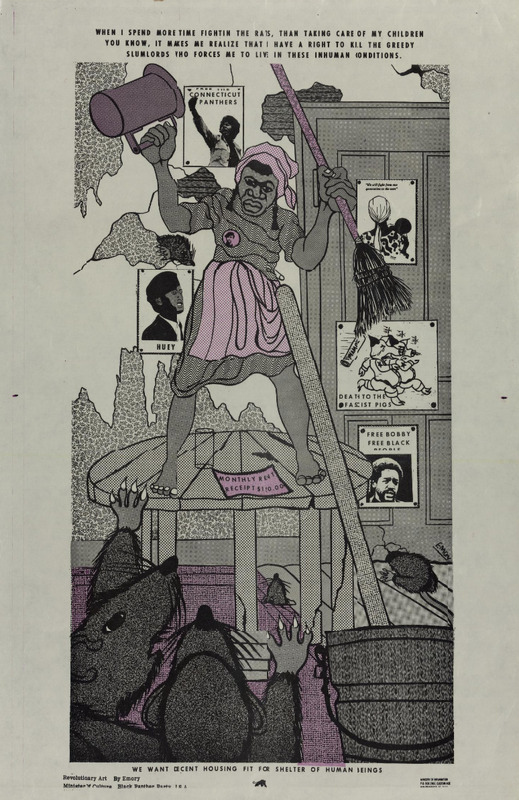

We can see this poster made by Emory Douglas titled "When I spend more time fightin the rats.." It was meant to highlight the inferior and unfair housing system that was set up to not allow people of color to live in nice clean homes and rather discarded to the unkept areas of town.

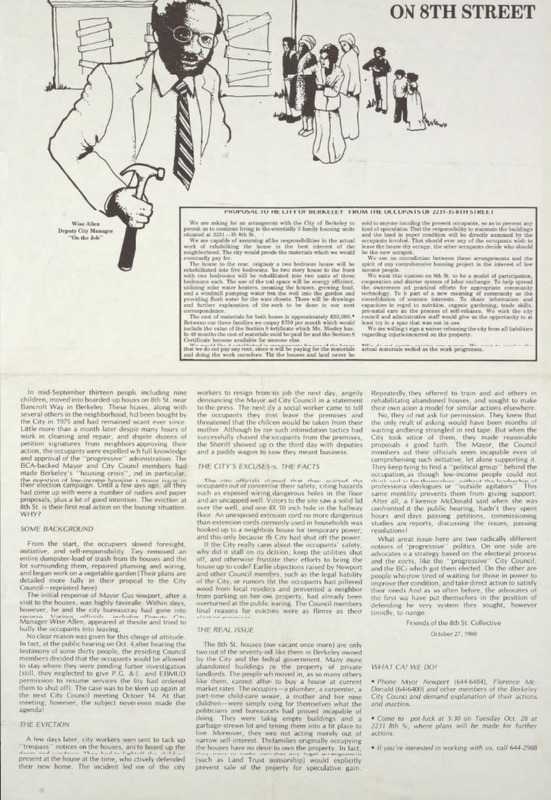

An instance of housing discrimination can be reflected through this poster titled "Clampdown on 8th street. " The poster explains that, in the mid-1970s, thirteen people (including nine children) moved into long-vacant, boarded-up houses on 8th Street in Berkeley, CA. These homes had been purchased by the city in 1975 and left empty, even during a growing housing crisis. The families cleaned out dumpsters of trash, repaired wiring and plumbing, and even started a garden. At first, the mayor responded positively, but within days the city reversed course. Utilities were cut off, workers tried to intimidate the families into leaving, and despite public testimony supporting the occupants, the City Council never followed through on its promise to let them stay.

Eventually the city posted “trespass” notices, boarded the homes back up, and sent the sheriff to forcibly evict everyone --- even threatening to take the children. Officials claimed it was about “safety,” but their own actions, like shutting off water and power, made conditions worse.

The real issue was that the families were doing for themselves what the city refused to do: turning abandoned, city-owned properties into safe and livable homes. They weren’t trying to profit, they were working-class residents, including a plumber, a carpenter, a child-care worker, and a mother with her kids, trying to build stability in a city full of empty houses. This poster highlights eviction and exposes Berkeley’s failure to address its housing crisis despite running on “progressive” promises.

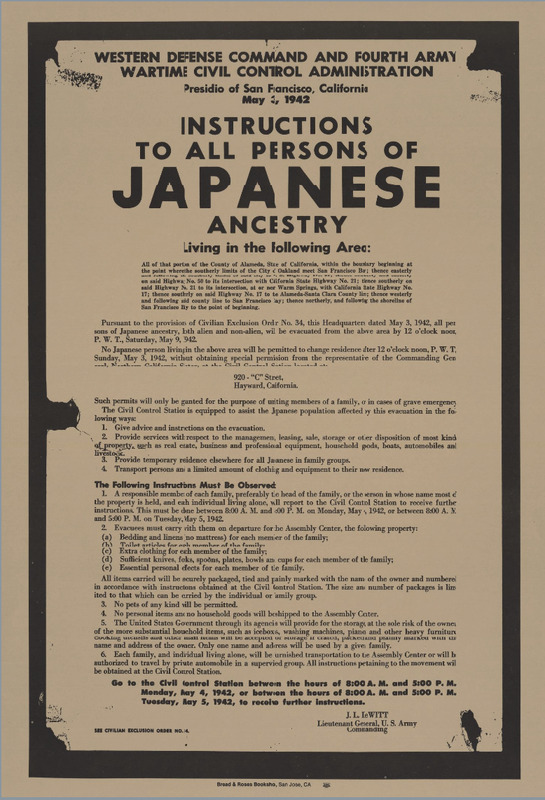

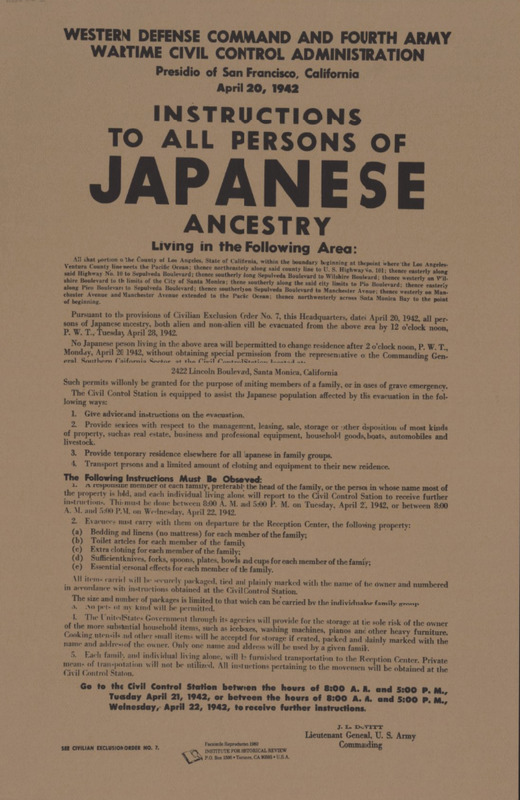

These posters are a bit different than the rest. One is from Southern California, Los Angeles county and the other is from Northern California, Alameda County. These are not posters created for community resistance but rather it is an example of the forced removal of Japanese people to U.S. prison camps. To explain, after Pearl Harbor the United States became very suspicious of anyone of Japanese descent and forcibly had any Japanese individual in the United States (whether they were a citizen or not) report to government facilities where they would be taken to camps to live for the next several years during WWII. The United States explained that this was done to protect the U.S. from Japanese spies, but with our present day context, we can understand this as a very early and intense form of housing discrimination.

Posted publicly by the Western Defense Command under Lt. Gen. J.L. DeWitt, the instructions laid out every detail of the evacuation process, where families had to go, what time they had to arrive, and even what they were allowed to carry with them.

The poster makes clear that Japanese Americans, including U.S. citizens, were given just a few days’ notice to abandon their homes, bring only what they could carry, and leave behind property, businesses, and community life. It also warns that anyone remaining after the deadline needed “special permission,” underscoring that their movement was fully controlled by the military.

This notice represents one of the thousands of exclusion orders issued along the West Coast after Executive Order 9066. Posters like this were how the government enforced the mass incarceration of over 110,000 Japanese Americans turning everyday neighborhoods into zones of removal and reminding people that their citizenship and rights could be stripped away overnight ( The National WWII Museum, 2025).