Mexican History in California

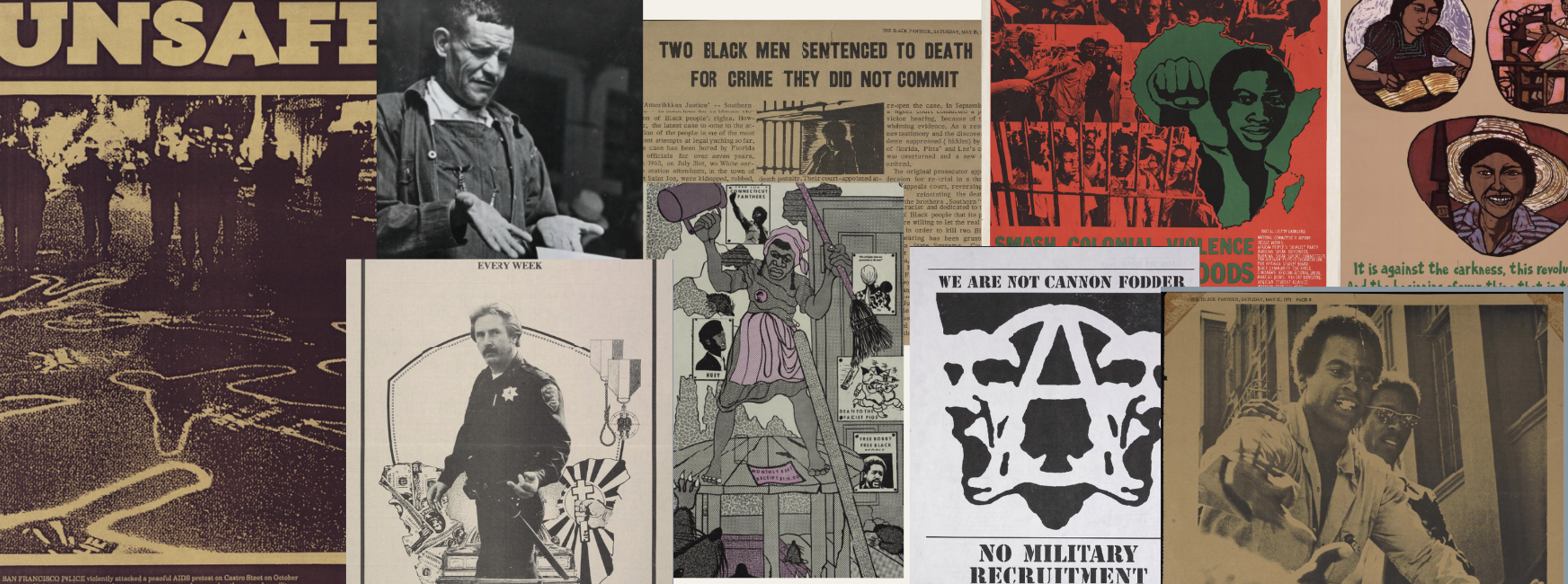

This poster draws directly from the spirit of the Nicaraguan Revolution, a movement that sought to overturn dictatorship, illiteracy, poverty, and U.S.-backed repression throughout the late 1970s and 1980s (American Archive of Public Broadcasting, n.d.)

The quote at the bottom is from Nicaraguan poet and revolutionary Ernesto Cardenal:

“It is against the darkness, this revolution… and the beginning of everything that is to come.” (Poster 1)

The images on the poster along with the text reading “In Solidarity with the Peoples of Central America,” captures a moment when Central Americans were striving not only for political transformation but for the possibility of a new social and cultural future (American Archive of Public Broadcasting, n.d.) By pairing this quote with scenes of everyday Mexican and Latino life in California, the poster represents the powerful solidarity networks that grew between Mexican American communities and Central American peoples resisting state violence and imperial intervention. It highlights how two Latin peoples, living in different places but shaped by intertwined histories of revolution and struggle, recognized their shared fight for dignity and a more hopeful future.

Furthermore, this political poster reflects the many stories and struggles that Latino and Latina communities faced in California. Its images; a woman working in what appears to be a factory, a man engaged in political life, a young girl reading, and another laborer on the shop floor captures the hard work, learning, and political participation that shaped Latino experiences throughout the twentieth century (the 1900s). Much of this community in California was, and still is, Mexican or Mexican American, also known as “Chicano.” This is due to proximity to the border in Southern California but also because of a long history that predates the U.S. Mexico border. To explain, there is a large population of Mexicans in California because before 1848, when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, California actually belonged to Mexico (although it is originally Native American land.) After the United States annexed the land, Mexicans were able to decide if they wanted to stay in the newly American-owned territory and gain citizenship, or go back to the new borders of Mexico.

Step 1. Saying goodbye

Here is an of Mexican men would be leaving Mexico for the Bracero program. It was a program created by the United States and Mexico to help fill the Labor shortage since many of the laborers went to serve in World War 11 from 1939-1945 (Gonzalez, 2013.)

The image shows the many young men saying goodbye to their mothers, wives, siblings and maybe children, to go work thousands of miles away to support their families and create a new life. This was the reality for many Latino men around Latin America who often sought new opportunities due to economic issues or even because of revolution like in the poster and how Nicaragua was going through a revolution. Revolutions although often brought violence and economic hardship and many times commuties sought saftey and work elsewhere in order to survive. This image shows what it meant to leave everything you know to begin a new journey of life.

Step 2. Finding work

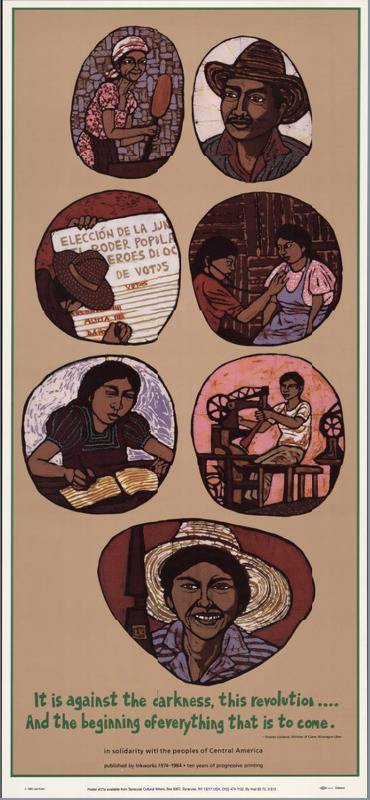

The next step in the process of leaving home to find work in the United States was stoping at the department of agriculture or industry where Latin men would be pointed to the nearest field or factory. Although these are the positions of work they ended up in, it was not by choice. The United States had discriminatory practices in the time and today where men and women who were Mexican or Latin, with papers or without were placed in what the US called "Unskilled Labor." This term is a bit confusing because if you know anything about working in the fields or a factory it takes alot of skill and resillience.

Here is a man in 1944 at the ranches hiring office showing his hands. Why may he be showing his hands at a jobs hiring office? His hands were his resume his only proof that he has lived a life of hard labor where is body bears the scuffs and toughness that has came with his labor.

In moments like this, the body itself became a record of labor, especially for Mexican and Latino workers who often lacked written documentation, formal training records, or legal protections. Employers judged a man’s ability by the calluses on his palms and the wear of his skin. This single gesture reflects the larger experience of Mexican laborers during the 1940s and the Bracero Program, where workers were depended on for their physical strength yet still faced discrimination and harsh conditions. His hands symbolize both survival and sacrifice, tying directly into the broader story of Latino/a labor in the United States and why solidarity became essential within and across Latin American communities.

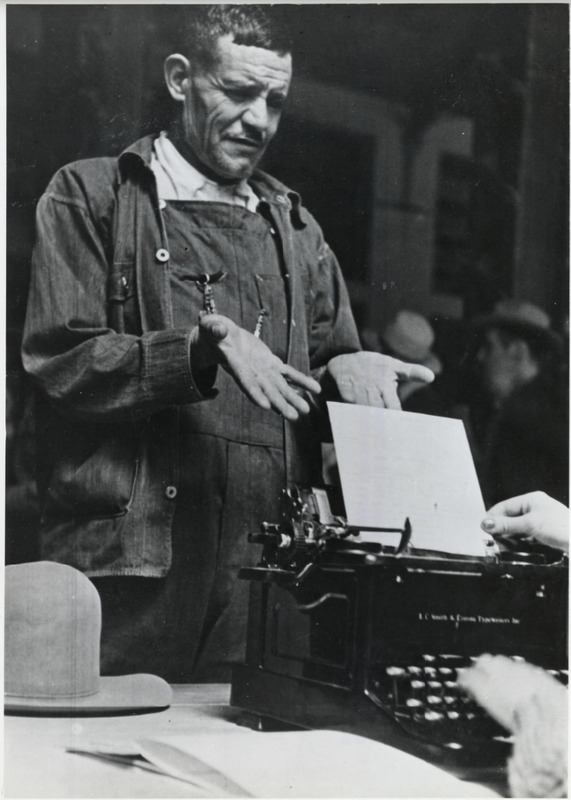

Step 3. Working the Lands

Here is a man proudly holding an enormous bundle of freshly harvested carrots, likely just one of many batches he gathered that day. Harvesting a batch like this took hours of bending, pulling, and carrying, and most workers repeated this labor four, 8 hours a day. During this period, many Mexican and other Latin American laborers were paid by the batch, meaning their wages depended entirely on how much they could harvest. They earned only a few cents for work that demanded intense physical strength and endurance, while growers made far more from selling the produce these workers picked by hand.

This photo captures not only the pride in his expression, but also the reality of field labor: no air-conditioning, no protection from winter cold, nothing to soften the heat of the sun or the long hours in the dirt. Day after day, workers like him stepped forward to do essential labor that fed entire regions, despite the low pay, harsh conditions, and lack of recognition. His posture and the weight of the carrots in his arms offer a glimpse into the resilience, skill, and perseverance that defined the lives of so many Latino agricultural workers.

Step 4. Washing up

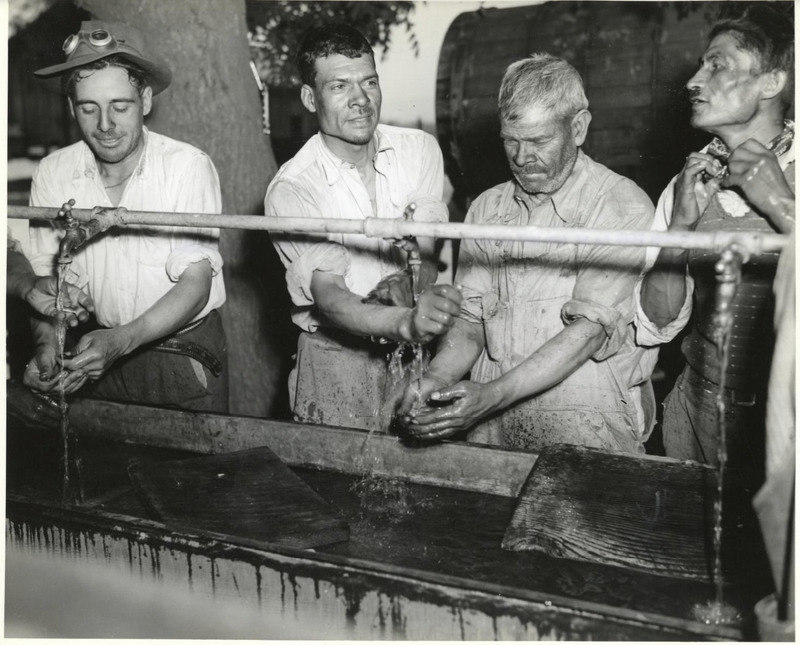

Here is my final image of the exhibit, which I think of as step four in the process of being a Latin or Mexican laborer: washing up after a long, hard day in the fields. Some of these men would return home to their wives and families, but many lived in labor camps alongside other workers. Their lives revolved almost entirely around work. Today, most people get to disconnect on the drive home, but for these men, work and living were only a few feet apart. They woke up before sunrise, labored in the heat and dust until sunset, and then stepped straight from the fields into crowded dormitories provided by the U.S., places often run-down and stocked with only the bare minimum of necessities, just enough to get through another day.

This moment, washing their hands together at the communal sink, shows a small pause in lives defined by exhaustion and routine. It reminds us how physically demanding and emotionally draining this labor truly was, and how little time these men had to rest or exist outside of their roles as workers. Yet even here, in this simple act of washing up, you can see the strength, endurance, and quiet pride that helped them get through each day.

This image brings the exhibit full circle. These men, like so many Central American and Mexican laborers, lived through exploitation, displacement, and sacrifice. Both groups faced harsh conditions, both worked to support families and communities, and both carried the weight of systems that depended on their labor but rarely acknowledged their humanity, and still making time to become politically involved in issues that impacted them and others. Ending with this image connects their daily realities back to that call for solidarity, a reminder that their struggles were never isolated, and that their resilience is part of a much larger story of Latin American perseverance and hope.